Originally published in Japanese on Mar. 4, 2022

Dominoes fall

Three days after Russia’s February 24 invasion of Ukraine, the global energy industry was hit with a shock: BP, a major international oil company, would withdraw its business from Russia.

Hearing the news, one energy industry player in Japan could not help but imagine the worst-case scenario. “This could spill over to Shell and Exxon too,” they thought.

Concerns about a domino reaction proved well-founded. Over the two days following BP’s announcement, Shell and Exxon Mobile announced they would also back out projects in Russia.

Sakhalin-2, a liquefied natural gas (LNG) project that Shell left, is also backed by Mitsubishi Corporation and Mitsui & Co., Ltd., two of Japan’s major trading houses. Immediately after the news of Shell’s departure broke, the two companies set out to gather information.

“The energy situation in Japan is very different than in the U.K. or the U.S.,” said an employee at one of Japan’s major trading companies. “That said, there’s no question that this is a difficult spot for both companies.”

While some international voices have pressed the Japanese companies to follow their Western peers, neither Mitsubishi nor Mitsui can easily back out of Sakhalin-2 for reasons neither prefers to discuss.

Regional dependence

Japan receives about 5 million tons of LNG annually from Sakhalin-2 based on long-term contracts. That accounts for just under 10% of all LNG handled in Japan. Considering crude oil from the Middle East accounts for about 90% of Japan’s total energy supply, Tokyo’s dependence on Russian LNG is relatively low.

However, if one examines the destination of the LNG shipped from Sakhalin-2, a different picture emerges.

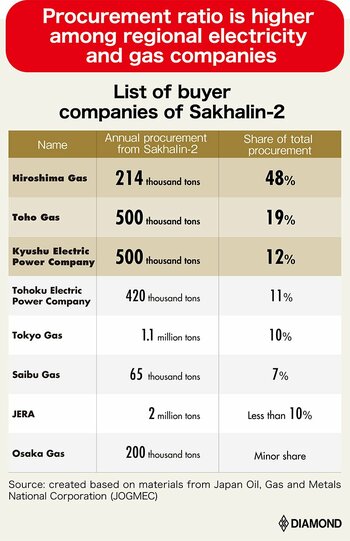

Sakhalin-2’s LNG is delivered by Mitsubishi and Mitsui to eight companies, including JERA, a joint venture between the fuel and power procurement departments of TEPCO and Chubu Electric Power, Tokyo Gas and Osaka Gas.

For JERA and Tokyo Gas, supply from Sakhalin-2 accounts for only about 10% of the total LNG they handle.

For regional gas and power companies, however, LNG from Sakhalin-2 is crucial. For instance, Hiroshima Gas procures 450,000 tons of LNG annually, and the 215,000 tons from Sakhalin-2 accounts for nearly half of that.

While JERA and Tokyo Gas, which handle massive amounts of LNG, could handle a hit to supply, regional gas and power companies like Hiroshima Gas would need to find LNG elsewhere if Mitsubishi or Mitsui backed out of Sakhalin-2.

Billions ‘lost in an instant’

It is possible to procure LNG from alternative sources using spot contracts, but for regional gas and power companies there is one problem: price.

LNG spot prices are at a historic high. JKM (Japan/Korea Marker), an index for the LNG spot price in Asia, exceeded $52 per 1 million British thermal units (Btu) for futures as of August 2022, a record high. That is more than five times higher than normal.

LNG has been recognized as a transition energy in the shift to a carbon neutral society thanks to its low carbon dioxide emissions, and companies around the world are already scrambling to acquire more.

Last autumn, a shortage of natural gas in the European market caused a “gas panic.” That pushed JKM up to $50 per 1 million Btu in October 2021, then a record high.

Then came the crisis in Ukraine. Western oil majors pulled out of Russia, raising concerns over reduced natural gas supplies from Russia to Europe via pipelines. The global battle for LNG will become even more intense, ensuring prices stay elevated.

Japan’s LNG industry is on edge. “A few billion yen (tens of millions of dollars) could be lost in an instant, just by procuring LNG on a spot contract at the current level,” said one person who works in the industry. Rising costs of a few billion yen are a matter of life and death for regional electricity and gas companies.

Hiroshima Gas expects a profit of 3 billion yen this fiscal year, and Saibu Gas expects 500 million yen in profits. Procuring LNG at the spot price risks sending both companies into the red.

Power and gas companies generally pass costs on to consumers, meaning energy bills would become at least twice as expensive. Soaring energy prices would hit regional economies particularly hard.

A withdrawal by Mitsubishi or Mitsui from Sakhalin-2 risks triggering a practical revolt in areas outside of Tokyo. As a result, the two trading companies have eschewed coming to a quick decision like the major international oil companies, and are instead consulting with regional gas and power companies, other buyers and the Japanese government.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine is taking place more than 8,000 kilometers away from Japan, and it is unlikely that Japan will be directly exposed to the horrors of war or that many refugees will come to the country.

Russia’s attempt to change the status quo by force is, of course, totally unacceptable. However, if Japan takes steps like those taken by Western countries and companies, the Japanese people must be aware that they will not escape unscathed. Soaring energy prices will surely hit regional economies, areas where economic growth is already lagging, particularly hard.

(Originally written in Japanese by Ryo Horiuchi, translated by Erklaren, Inc. and edited by Connor Cislo)