Originally published in Japanese on Feb. 14, 2022

Flattening hierarchy

At Toyota Motor, a “large-scale meeting” that includes online participants is held every Tuesday to share progress on major projects within the company. It was originally a closed meeting of about 20 directors, but it transformed into a huge event with more than 200 participants, including mid-ranking executives overseas, at the wish of President Akio Toyoda.

The former directors’ meeting was often an occasion for whichever department was announcing a new project to obtain the implicit understanding of the other directors. “Maneuvering to win support from the majority was indispensable,” said a person familiar with the situation. “That way your boss’ presentation would get the approval of the other directors. Ahead of one meeting, we even persuaded a vice president to say, ‘That sounds good’ during a presentation.” Although some may consider it a fault particular to large companies, this was the process through which decisions were made and the company’s direction was decided.

Looking back further, decisions used to be made by the “inner sanctuary.” In the early 2000s, final decisions were made through a council composed of Shoichiro Toyoda (Akio’s father), Tatsuro Toyoda (Shoichiro’s younger brother), and Akio Toyoda of the Toyoda family, as well as Hiroshi Okuda, Fujio Cho, and Katsuaki Watanabe, the three former presidents from outside the founding family. However, “conclusions were fixed in advance, because Mr. Cho typically sides with the Toyoda family,” said another person familiar with the situation.

Akio Toyoda may have intended to breathe life into the meetings that had become mere formalities by opening them to over 200 middle-managers. Before the change, the number of veteran directors was significantly reduced from 2020, and Toyota currently has 10 top-ranking directors. The change was supposed to flatten the hierarchy among the directors to make a clean break from outdated thinking, and to rejuvenate the top management.

However, practically no one among the top directors can express their honest opinions to Akio Toyoda, according to sources familiar with the situation. “The meeting with 200 participants tends to be a chance to show off to the president, and important decisions are not made there,” one of the sources said. “I would imagine that the concept of flattening the hierarchy to ensure free and vigorous discussion was used as a cover, and the true intention was for Mr. Akio to decide everything alone and reinforce the centralization of the Toyoda family.”

Whatever the intention, the result was to deprive the top management of opportunities to engage in the decision-making process. In what could be described as a “side effect” of the organizational reform, the meeting now functions as a facade of a decision-making body, the sources said.

The dominance of Akio and the Toyoda family over management continues to grow. Excessive involvement in management by founders, however, is not without risks.

Family politics

Akio Toyoda holds only 0.17% of Toyota’s outstanding shares, and the Toyoda family as a whole, including Shoichiro, is thought to hold “about 2%,” according to a person familiar with the situation.

“Akio currently behaves like an owner who holds a large amount of Toyota shares,” said another individual familiar with the situation at the automaker. “The company is moving closer to an atypical situation in which it’s dominated by the founding family, which is beyond the oversight of the board of directors.”

The growing control of the founding family can be seen in three places. The first is in the information campaign carried out by the “Toyota Times,” a Toyota-owned media outlet. The outlet’s website is filled with descriptions of the history of the Toyoda family and their philosophy.

The second is in the Woven City project, which is led by Akio’s eldest son, Daisuke Toyoda. The Toyoda family has invested 5 billion yen ($40 million) of its own funds in the project.

The third is seen in the exclusion of those from the “branch families” like Eiji Toyoda, who helped bring Toyota to prominence, from the company history. Only the main Toyoda family is recognized as the true heirs to the auto empire. Presentations made by Akio in recent years have pushed the idea that Sakichi Toyoda, who invented the automatic loom, Kiichiro Toyoda, who moved into the auto industry, Shoichiro, Akio and Daisuke are the direct line of the head house of the Toyoda clan.

“Akio is quite suspicious of others, and he only trusts his relatives and a very small group of people who would never betray him,” said another person familiar with the situation at Toyota. “It’s probably because [Hiroshi] Okuda, the former chairman, tried to separate corporate management from the founding family.”

Blood is thicker than water. In hoisting the standard of the head house of Toyoda, Akio may be aiming to unify the company’s 370,000 employees and develop a sense of solidarity.

‘Stretched to the limit’

However, it is far from clear whether the absolute authority premised on a flattened organization can solve Toyota’s outstanding issues. The company is expanding its operations like never before. It will be difficult for a single command point overseeing a flattened organization to cope.

The company is certain to press forward in expanding its conventional auto business for at least the next two years as production recovers from the COVID-19 pandemic (Toyota is currently revising down its production forecast based on the semiconductor shortage and other factors).

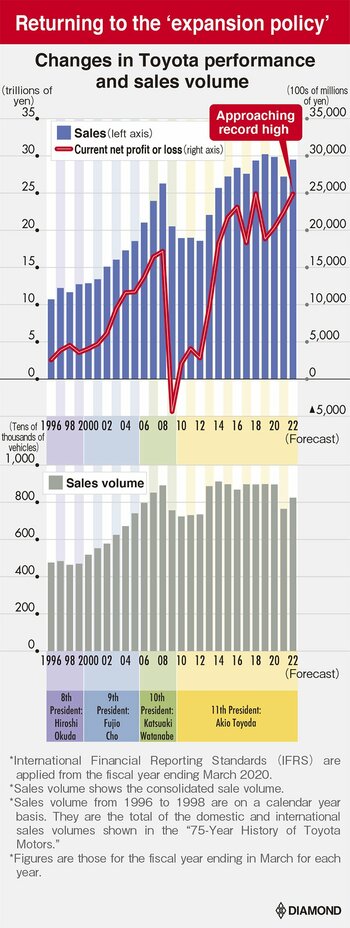

When Akio became head of Toyota in 2009, new capital investment had stopped because “the lines of communication had been stretched to the limit [and the organization could not keep up with its own growth],” according to an individual who was a senior Toyota executive at the time. The company is now working to expand for the first time since the global financial crisis. Its market capitalization temporarily topped the 40-trillion-yen milestone for the first time in January, and the company is doing well as it pushes aggressively into electric vehicles (EVs).

Uncharted territory

The auto industry is undergoing major changes, and Toyota’s expansion is not limited to its conventional auto business.

Two fundamental shifts are hitting the auto sector at the same time: electrification and decarbonization. The value in mobility is moving from hardware to “go forward, turn and stop,” to the software that governs automated driving and mobility services. In that context, Toyota has stuck firmly to its belief in “ultra-vertical integration,” which means the company is sure that it owns all technologies and products that are important to its success.

In addition to manufacturing its own semiconductors and batteries ― the core hardware for electrification and automated driving ― Toyota wants to advance into the upstream supply chain, including procuring rare materials and developing its renewable energy business. The company naturally aims to become the dominant player in software, the brains of mobility.

As a result, Toyota’s rivals are no longer just conventional automakers. The company will compete with a wide variety of other businesses, including the GAFAM IT giants (with Facebook changing its name to Meta) or Tesla, as well as actors from the horizontal division of labor, like Nidec Corporation, Sony Group and Foxconn.

Toyota is entering uncharted territory, which may prove a challenge for Akio Toyoda. He is not a founding president with proven leadership skills.

As of March 2002, prior to introducing the operating officer system, Toyota had a whopping 58 directors, among which were 8 executive vice presidents, 5 senior managing directors and 14 managing directors. Akio appeared at the bottom of this list as a managing director, then only 45 years old. It took this many executives to steer the company, even when it was just focused on the single business of making and selling cars.

It is unclear what impact the growing dominance of the head Toyoda family will have of the auto giant’s future decisions and corporate governance.

(Originally written in Japanese by Fusako Asashima, translated into English by Erklaren, Inc. and edited by Connor Cislo)