The yen has depreciated around 10% against the U.S. dollar since the start of the year, pushing the USD/JPY exchange rate to a 20-year high. The yen has been the weakest of major currencies so far in 2022 and only a handful of emerging market currencies, including the Turkish Lira and the Argentine Peso, have eclipsed the yen’s slide against the dollar.

Perfect storm

Two forces have conspired to create a perfect storm for yen depreciation. The first is a sharp repricing in U.S. interest rates, prompted by the Federal Reserve’s signaling that an aggressive policy tightening cycle is in the cards in the face of multi-decade-high rates of inflation. A sharp rise in U.S. yields — the 2Y U.S. treasury yield has soared from close to zero a year ago to more than 2.5%p.a.— has widened the yield gap between Japan and the U.S., in large part because of the Bank of Japan’s yield curve control policy. With Japanese yields largely unable to rise alongside global yields, the currency has been the only release valve for markets. Growing divergence between a Fed with no time to lose in tightening policy, and a BOJ that is apparently in no rush to wind down massive monetary stimulus, has been reflected in a sharp adjustment of the yen.

The second factor weighing on the yen is the impact of sharply higher energy prices on Japan’s trade balance. The prices of a wide array of commodities have soared this year as markets have grown increasingly concerned about the impact of the Russia-Ukraine conflict on supplies. At their peak, crude oil prices had risen almost 60% this year, though they have since retraced somewhat. As a major importer of fuel and other commodities, Japan’s external balances have taken a hit from this year’s surge in commodity prices. In January, Japan printed a near record-wide trade deficit — the trade balance has only been more in the red on one occasion over the past two decades. This dynamic has increased the need for Japanese importers to source foreign currency to pay for imports. In other words, importers have had to sell yen to finance higher energy and commodity import bills, further putting pressure on the yen.

The yen’s slide versus the dollar through March alone was remarkable in one other aspect: the dominance of local market participants in fueling the yen’s slide. This is quite a different setup compared to the experience in recent years. The bulk (around 60%) of the March move higher in the USD/JPY exchange rate has happened during Tokyo trading hours. But the last time USD/JPY rose close to the 125 level almost seven years ago, the move happened almost entirely in New York and London trading hours, perhaps reflecting the dominance of speculative foreign investors in the move. This time is different. Yen weakness has largely reflected what we think of as fundamental factors: central bank policy divergence, and Japanese corporate demand for foreign currency alongside sharply higher import bills.

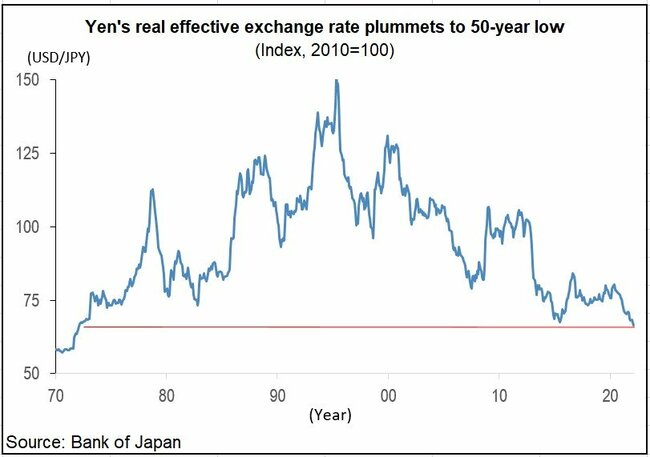

While the yen’s slide versus the dollar has grabbed headlines, the plunge in the yen’s real effective exchange rate has been even starker. This rate measures the yen against a basket of global currencies after controlling for differences in inflation rates, and it is currently at low levels not seen since the 1970s. This would ordinarily be very good news for foreign tourists. The purchasing power of a dollar (or, perhaps more relevant, the renminbi) in Japan has reached multi-year highs. Quite literally, foreign tourists in Japan can get a lot more for their buck. But with borders that have been essentially locked through the COVID-19 period, meaning a total absence of tourists in Japan, there have been no yen-buying tourism inflows that might otherwise have given some support to the yen.

If markets continue to price in an aggressive tightening cycle from the Fed and U.S. interest rates continue to rise, halting the yen’s slide will be akin to fighting a losing battle. The peak in market volatility around the end of the Japanese fiscal year in March may be behind us, but a fundamentally negative backdrop for the yen may nonetheless carry through to the new fiscal year. This will largely reflect continued policy divergence between the central banks in the U.S. and Japan, as the Fed embarks on a rapid attempt to unwind COVID-19-era monetary stimulus and mop up emergency liquidity. If this plays out, the risk is that a renewed upward push in U.S. interest rates could ultimately pull the USD/JPY exchange rate into the 130s, levels that have not been seen in 20 years.

Ben Shatil is Head of Japan FX Strategy at J.P. Morgan. Ben joined J.P. Morgan in 2011 after working as a Research Fellow at the University of Tokyo and Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy, Singapore. He holds degrees from the University of Cambridge and Yale University. The views expressed here are his own.