Originally published in Japanese on Jul. 9, 2022

Looking at legacy

On July 8, Shinzo Abe, the longest serving prime minister in Japanese history, was shot and killed in the city of Nara. His murder, committed in the middle of a campaign speech ahead of the July 10 upper house election, was an act of terrorism and an assault on democracy, and it is unforgivable. I condemn the perpetrator in the strongest terms, and also offer sincere prayers that Abe’s soul may find peace. Those concerned for the future of Japan are now keenly feeling the loss of Abe.

In reflecting on Abe and his legacy, most look to his eight-year administration from 2012 to 2020, his second term as premier. For me, however, the first Abe administration that began in 2006 left an even stronger impression.

Abe’s first cabinet clearly embodied conservative thinking in Japan, taking on initiatives like revisions to the Basic Act on Education and proposing the Act for Establishment of the Ministry of Defense. It was true to its name: the “cabinet for the creation of a beautiful country.” Until then, successive administrations had all announced their own “reforms,” but they rarely tackled issues fundamental to the national character.

The youngest prime minister in Japan’s postwar history — Abe reached the pinnacle of power at the age of 52 — who unabashedly put forward a new vision for the nation, Abe felt like something new. His call to “break away from the postwar regime” was overwhelmingly effective. Many Japanese expected his tenure to mark the beginning of a new era.

If former Prime Minister Junichiro Koizumi, Abe’s predecessor, was a “star” who was popular nationwide, Abe could be called a “spiritual leader” who was supported by the conservative faithful.

He embarked on needed reforms, such as creating the National Security Council and reforming the bureaucracy, in rapid succession. He galvanized the movement to revise the constitution, an objective that was his political lodestar. This was the moment when many felt the power of politics to change the nation.

Defeat and a triumphant return

However, as if to match the speed of these reforms, the scandals and gaffes of members of the cabinet continued apace, and Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) suffered a devastating defeat in the upper house election of 2007. Abe then announced his resignation as prime minister because of a deterioration in his health due to a chronic condition. His first administration ended only one year after its inauguration.

Abe was unquestionably distressed by the criticisms against him after his resignation: He was known as “the prime minister who threw the administration aside,” and his resignation was termed “the end of Abe.” But he once again rose to the top of the LDP despite his health issues, winning a come-from-behind victory in the party’s 2012 leadership election over former Secretary-General Shigeru Ishiba. In the general election held later that year, he led the LDP to victory and retook the administration from the Democratic Party of Japan.

The second Abe administration, beginning in late 2012, stuck to its goal of overcoming deflation through the “three arrows” of Abenomics; monetary easing, fiscal stimulus, and structural reforms to stimulate investment in the private sector. The program succeeded in correcting the excess strength in the yen, which had previously risen to 75 yen per dollar, and the Nikkei Stock Average began to skyrocket.

With the yen now weakening rapidly, both supporters and opponents of Abenomics have naturally grown more vocal. But the initiative clearly improved employment conditions and company earnings in Japan, which were important tasks for the administration. Even those who opposed Abe politically must recognize these achievements.

Personal touch

I was keen to watch Abe’s behavior after he stepped down as prime minister in September 2020. Although he entered the political wilderness after his first administration, Abe remained influential after his second administration. He effectively chose Yoshihide Suga, his long-time chief cabinet secretary, as his successor.

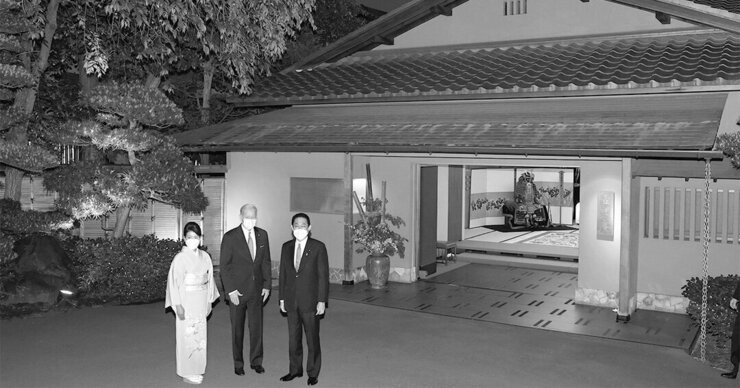

With the support of the LDP’s largest intraparty faction, Suga followed Abe as prime minister. The current premier too, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, also could not openly defy Abe. The “Reiwa Kingmaker” held influence over various fields, from domestic affairs to foreign policy. He had recently led discussions on increasing defense spending and policies for sharing nuclear weapons. One could say that Abe’s presence continued to grow, even after stepping down as prime minister.

In contrast to Kishida, who is calm and rarely becomes emotional, Abe often voiced harsh criticisms of the opposition parties and his political opponents. There is no question that both his personal attitude and his political works are subject to both praise and censure. However, I believe that giving the Japanese people and opportunity to think deeply about the national character is laudable.

Abe and Kishida both won their first elections to the National Diet in the same year, and Abe once joked about the latter that “the best-looking guy was Fumio Kishida, and the best-hearted guy was Shinzo Abe.” I wish that he could have lived longer so I would have seen how the “best-hearted guy” would continue to “create a beautiful country.”

I once heard an interesting story from Akie Abe, the wife of the former prime minister.

She told me that Abe “was envied throughout the world because he had a good relationship with Donald Trump. Trump was not friendly to everyone, and [Abe] made considerable effort to get along with him.”

Of course, Abe did not conduct personal diplomacy only with the former president of the U.S. Abe’s style of personal interaction helped him maintain good relations with leaders around the world, including Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Effort makes you strong. Effort allows you comeback, even after a major blunder. Effort helps you win respect from people around the world.

It seems that I still have many things to learn from life of Abe.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kenichi Ogura, translated into English by Erklaren, Inc. and edited by Connor Cislo)