Policy-based cycle

The recommendation to 'Buy Japan' is one that most seasoned Japanese equity investors will have heard repeatedly around this time of year since the bursting of the Japanese asset bubble in the late 1980s. It is a recommendation that can be justified through various lenses, be it relative underperformance versus global peers, attractive valuations, or the latent potential for improvement in returns. However, it is a recommendation that has rarely worked. Nevertheless, we believe that there may be cause for some cautious optimism with regard to Japanese equities markets. Based on previous equity market cycles in Japan, we believe that 2023 may herald the start of a new dawn for the country’s equity market.

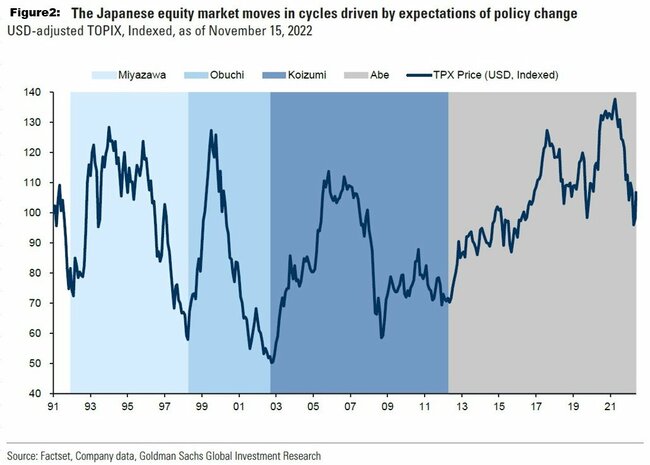

This view was first articulated in a Goldman Sachs Research report published in the fall of last year. In the report, we argue that since the late 1980s, the Japanese equity market has demonstrated strong cyclical qualities. Historically, it has usually been a change in fiscal or monetary policy and/or expectations of structural reform that has triggered the start of the upward phase of a new Japanese equity market cycle. Each new cycle is preceded by policy uncertainty caused by a series of crises that can be either domestic or global in nature.

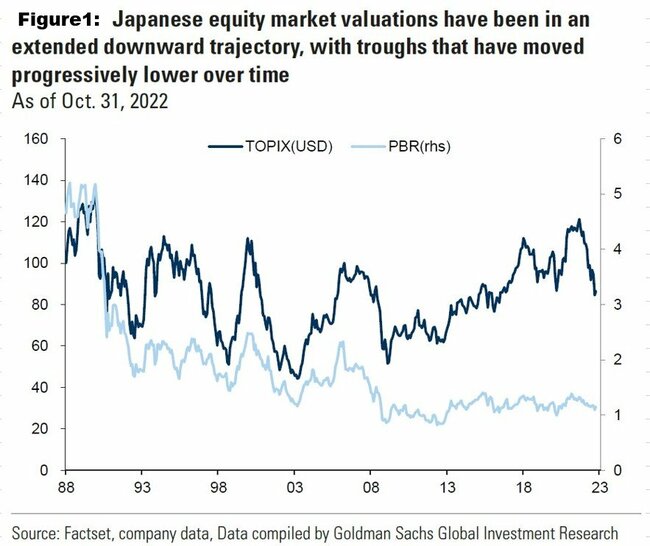

Our analysis suggests that expectation levels around policy change and structural reform are important inputs in asset allocation decisions regarding Japan, particularly for foreign investors. As can be seen in the chart below, Japanese equity valuations have been in an extended downward trajectory since the late 1980s, but the market has still managed at least four major U.S. dollar-adjusted rallies during this period. However, the rallies have started from progressively lower valuation levels. We would argue that foreign investors do not buy Japan when it is perceived to be inexpensive on an absolute or relative basis. Rather, our view is that foreign investors buy Japan when they believe that it is about to undergo a period of major change.

The pattern tends to be similar in each cycle: TOPIX declines before the start of a new cycle as political pressure builds for a decisive policy response. This eventually results in a change of political leadership. The downtrend to technically over-sold levels remains in place until there are signs of meaningful policy action from the new political leadership. The implied promise of structural reform or fiscal stimulus begins to attract foreign investor flows back into the Japanese market, which in turn provides support for TOPIX.

The upward momentum of the cycle continues until policy action either fails to keep pace with investor expectations, or there is an exhaustion of incrementally positive news flow. The subsequent disappointment causes the market to retreat from over-bought levels and stalls foreign investor inflows. Another series of economic crises accelerate the market's decline, foreign flows reverse, and political pressure builds again until the start of the next cycle.

We believe the four main rallies witnessed since the late 1980s represent four major market cycles in Japan which we have categorized as 1) the Miyazawa cycle (1992-1998), 2) the Obuchi cycle (1998-2003), 3) the Koizumi cycle (2003-2012) and 4) the Abe cycle (2012-2022).

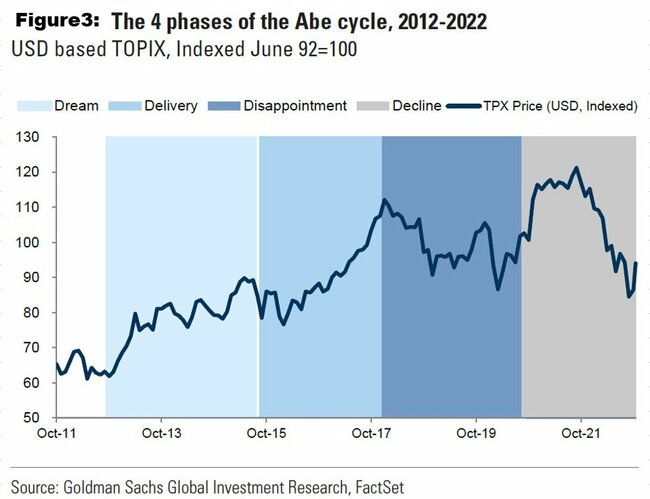

The upward momentum and subsequent retreat can also be mapped across four distinct phases. It usually shifts in investor sentiment regarding the possibility of fiscal stimulus, monetary policy and/or structural reform that dictate price action through each phase of the cycle. We have therefore categorized these phases as: 1) the Dream, 2) the Delivery, 3) the Disappointment and 4) the Decline. The Japanese equity market tends to produce its best absolute U.S. dollar-adjusted returns during the first 2 phases of these cycles, before pulling back significantly in the latter phases.

To better illustrate these phases, let us look specifically at the most recent cycle that began with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s second administration.

Abe returned to power in late 2012 with a comprehensive plan to revitalize the Japanese economy and the Japanese equity market. Abenomics consisted of three arrows: 1) aggressive monetary policy, 2) fiscal consolidation and 3) a strategy for growth. The Dream phase of the Abe cycle lasted from the end of 2012 until mid-2015 and focused on the first two arrows. The Delivery phase involved the Abe government pushing through a number of meaningful pieces of corporate governance reform including the adoption of the Japan Stewardship Code in 2014 and the Japan Corporate Governance code in 2015. However, there was a period during the Delivery phase when foreign investor flows turned negative, coinciding with the consumption tax increase from 5% to 8%.

The Disappointment phase appeared to kick in from early 2018 as investors expected faster or more meaningful corporate governance change than what was actually being delivered. Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga took over in September 2020 and the market reaction to his plans for economic growth was initially positive. However, his response to the Covid pandemic was unpopular with the Japanese public, and he was replaced by Fumio Kishida in September 2021. In U.S. dollar terms, TOPIX has fallen sharply since Kishida took over as prime minister. In the absence of a clear policy-driven agenda from the Kishida administration, we assume that we are currently positioned toward the end of the Abe cycle.

The Liberal Democratic Party’s decisive victory in the Upper House elections last year gave Prime Minister Kishida both the mandate and the runway to implement policy change with the potential to kickstart a new market cycle. And while his government’s approval ratings have declined markedly in recent months amid crises of varying sizes, this very unpopularity – or indeed the establishment of a new administration – could provide the impetus for meaningful policy change. Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan’s tweak to yield-curve control last December came as a significant surprise to the market. While our economists’ baseline scenario does not call for an imminent, more fundamental shift in the bank’s easing stance, they do not rule out the risk of further abrupt surprises.

Any cyclical shift that was accompanied by a strengthening of the yen could offer U.S. dollar-denominated foreign investors an attractive combination of local currency price appreciation combined with meaningful foreign-exchange gains. A similar dynamic was seen in 1998-1999 as a coordinated intervention to stabilize the yen brought the dollar-yen pair down from 147 yen in August 1998 to just 102 yen in December 1999. At the same time, the Obuchi administration implemented 24.5 trillion yen of fiscal measures to kick-start the economy following the Asian Financial Crisis. TOPIX rose 73% over this period in local currency terms but gained 126% on a U.S. dollar-denominated basis.

Bruce Kirk is Goldman Sachs' Chief Japan Equity Strategist. He has spent the majority of his professional career in Asia, based predominantly in Tokyo and Hong Kong, where he has held a number of positions on both the buy-side and sell-side, including Portfolio Manager at Balyasny Asset Management (Asia), Head of Goldman Sachs (Japan)'s Principal Strategies Department, founding Partner at Azentus Capital Management and Co-Head of Equity Research at KBC Securities (Japan). The views expressed here are his own.