Originally published in Japanese on May. 3, 2023

A ‘major issue’

“Doing something with everything we bought is a major issue…”

Kazuo Ueda, now governor of the BOJ, offered an unusually strong statement at a Diet hearing before taking office in late February. While many of his answers to questions from lawmakers stayed in safe territory, the “major issue” referred to the BOJ’s policy of purchasing ETFs.

Shingo Ide, the chief financial engineer at NLI Research Institute, estimates that the total amount of ETF holdings accumulated by the BOJ had ballooned to 53.1 trillion yen (market value) by the end of March 2023.

It is unprecedented globally for a central bank, the “lender of last resort,” to “prop up” stock prices.

More than a decade after the start of the ETF purchase program, the BOJ is now the largest shareholder of Japanese companies, holding about 7% of the total market value of listed stocks in Japan.

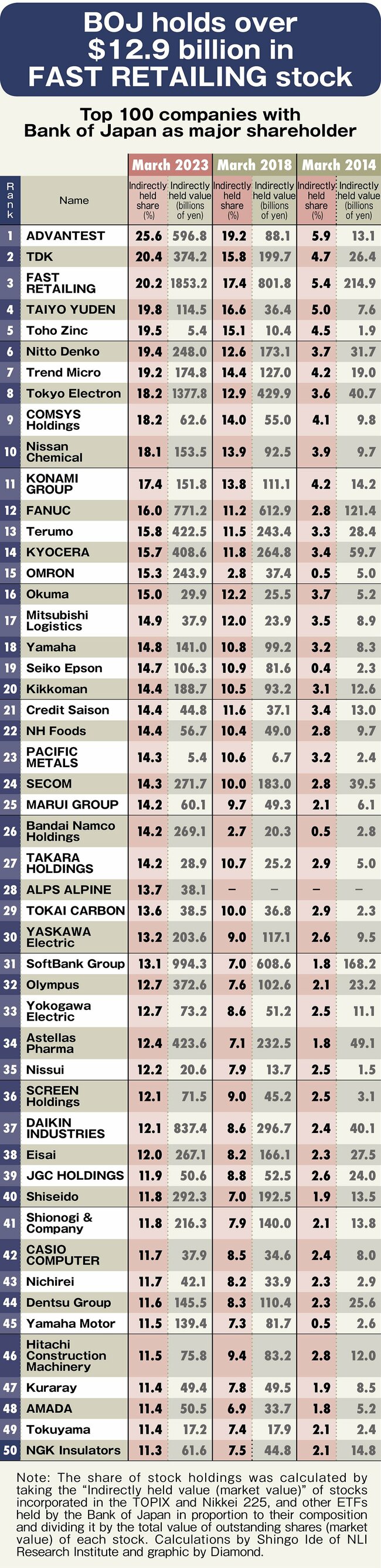

At which companies does the BOJ reign as the “major shareholder?”

Below are the top 50 companies in which the BOJ is the largest shareholder. Data from March 2014, one year after the start of the quantitative and qualitative monetary easing of former Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, and March 2006 are also included.

Topping the list is ADVANTEST, a major manufacturer of semiconductor testing equipment. The BOJ held 25.6% of its outstanding shares as of March 2023. It is followed by TDK, a major electronic components manufacturer, at 20.4%, and FAST RETAILING, which operates the UNIQLO brand, at 20.2%.

The BOJ’s massive buying stands out compared to five years prior. The central bank's indirect holdings of FAST RETAILING stock have topped 1.8 trillion yen, meaning it has purchased more than 1 trillion yen of the company’s stock over the past five years.

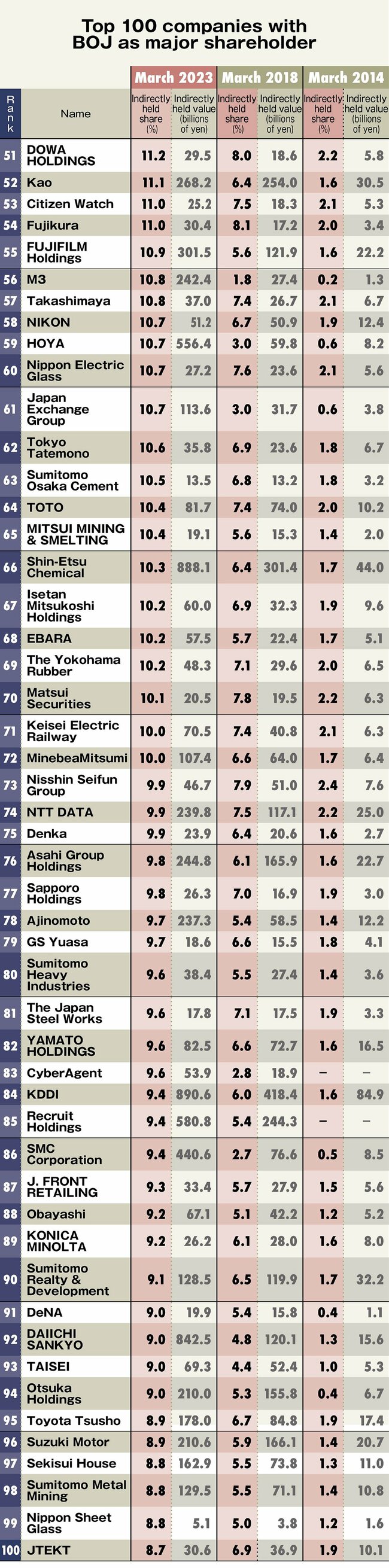

The number of companies in which the BOJ's indirect holdings exceeded 10% also increased to 72 from 28 five years ago. They include prominent companies such as Tokyo Electron, FANUC, Yamaha, and Kikkoman. The following are the remaining 51-100th ranked companies.

Policy costs

The BOJ's ETF purchases began in 2010 under former Governor Masaaki Shirakawa. The idea was that improved investor sentiment would ripple effect on the broader Japanese economy. There was initially a cap on annual purchases of 450 billion yen, but the buying sharply accelerated when Kuroda became governor in 2013. Annual purchases increased to 1 trillion yen and then tripled to 3 trillion yen with additional easing in the fall of 2014. The amount was further increased to 6 trillion yen in the summer of 2016, and cumulative purchases passed the 10 trillion yen mark in the fall of the same year.

Some have noted that large purchases of ETFs that do not account for the performances of individual stocks have side effects, such as decreasing market function. With criticism mounting, the BOJ has bought a few ETFs since the spring of 2021. The current annual purchase amount is “0-12 trillion yen,” but in effect, there has been a move toward “stealth tapering.”

The most recent moves on ETF purchases came on March 13 and 14, when the BOJ bought 70.1 billion yen each day in response to the market turmoil caused by the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in the U.S. Because of this situation, the consensus among the market participants is that changes to yield-curve control and negative interest rates are higher priorities.

Still, there is one problem that cannot be overlooked: the “cost” of ETF purchases. These costs are custodial fees—fees paid by the BOJ to asset managers and trust banks.

The dividend income from the ETFs purchased by the BOJ, minus custodial fees, is paid into Japan’s national treasury. The higher the custodial fees, the less that is paid into the national treasury, leading to a decrease in national revenue. Because of the cost of the balance, the more time spent tampering with policy, the greater the cost.

Hidden costs

The BOJ began purchasing ETFs under new rules in December last year with the goal of curbing the program’s operating costs. Instead of selecting stocks to be purchased based on the market's distribution ratio and other factors, they are now bought based on which has the lowest custodial fee ratio.

However, there are limits to how effective this is. According to Ide’s estimate, the BOJ paid 53.5 billion yen in custodial fees in fiscal 2022. As the balance has built up, the burden has increased by 23 billion yen from 30.5 billion yen five years ago (fiscal 2017).

Some estimate the BOJ had paid a cumulative total of 300 billion yen in custodial fees from December 2010, when the BOJ began its ETF purchase program, to the end of 2022. Within the asset management industry, these fees are called the “BOJ subsidy,” and some see it as a blessing in disguise.

Furthermore, although the custodial fee rates are lower, the trademark usage fees to index providers are not insignificant due to the huge amount of holdings. The BOJ has been paying “commissions” to the Tokyo Stock Exchange, the provider of the TOPIX, and to Nikkei Inc., which manages the Nikkei 225. A policy in which a public institution favors a particular industry by chance is a major problem.

In addition, for BOJ ETFs, managing companies exercise their voting rights in accordance with the Stewardship Code (guidelines for institutional investors). While he sees no major problem with this structure itself, Ide notes that “it is a major contradiction that the BOJ's policy objectives themselves are not reflected through the exercise of voting rights, even though the BOJ holds more than 50 trillion yen in ETFs.” This is because, under the ETF structure, it is the investment management companies that actually manage and operate the ETFs that have the right to decide how to exercise voting rights.

The path to an exit is not straightforward. Ide believes that the BOJ under Ueda will likely move to act on the ETF policy only after the start of normalization, which includes addressing yield-curve control and negative interest rates. He suggested that “ETFs could be separated from the BOJ and transferred to a third-party institution for management” to limit market confusion.

At the same time, he noted that another option would be to replace ETFs with individual stocks. This would eliminate the need for ETF custodial fees to be paid to the investment management companies and prevent the outflow of tens of billions of yen worth of national wealth each year.

If they are shares rather than ETFs, a third-party organization that holds the shares could be directly involved in the voting process, although the specific method may be debated. This would clear a path to fulfilling the investor engagement (dialogue with companies) that the government itself has been promoting.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kohei Takeda, translated and edited by Connor Cislo)