Originally published in Japanese on September. 19, 2023

Rush to raise yields

The BOJ has explained that the current inflation has been (undesirable) cost-push caused by increases in raw material and energy prices. As these prices have started to decline globally, this inflation will eventually decrease toward the end of this year in Japan as well. Additionally, the BOJ has constantly communicated that (desirable) demand-pull inflation driven by the virtuous cycle of wage and price hikes will increase next year, although the central bank’s confidence about this outlook is low due to uncertainty.

If that is the case, it would have been more prudent for the BOJ to adjust its policies after confirming data that would support such a virtuous cycle. The author had anticipated that this might happen as early as mid-next year. The policy decision made in July, while still under the influence of cost-push inflation and weak consumption demand, appears premature from the perspective of achieving the target of stable 2% inflation, deviating from the central bank’s previous communications.

The BOJ’s surprise move, which amounted essentially to a 10-year yield hike, despite signaling the continuation of the status quo until the last moment, seems to have been driven in part by the Bank’s effort to simultaneously achieve three objectives with its monetary policy. These three goals are: 1) achieving a stable 2% inflation rate, 2) improving the functionality of the bond market, and 3) correcting excessive yen depreciation. Regarding the policy measure, number one involves maintaining a stable low-interest rate, number two involves curbing fixed-rate operations, and number three necessitates interest rate hikes. Among these, two and three can be realized through an expansion of the fluctuation range without contradiction between them. However, as number two had already been improving, fixed-rate operations had been only rarely conducted since March this year. Thus, many market participants believe that the intention of the July policy adjustment was to increase the focus on number three: correcting excessive yen depreciation.

The fact that the July response appeared to be aimed at addressing excessive yen depreciation but instead resulted in further yen depreciation can be attributed to the ambiguous nature of the policy adjustment. Therefore, market expectations are increasingly focused on bolder policy adjustments, such as changes in the 10-year interest rate control and the removal of negative interest rates, as part of the path toward normalization.

In this article, I would like to discuss the objectives behind the July policy adjustment, the interpretation of its content, and the ideal steps for normalization.

Japanese vs. U.S. inflation

The primary objective of monetary policy is price stability. Since 2013, price stability has been defined as 2%, in line with the global standard. As Ueda has pointed out, this target has yet to be achieved. Even though current inflation exceeds 3%, this is primarily because cost-push inflation is generally not sustainable. The governor has explained that raising interest rates under cost-push inflation would have a negative impact on the economy and employment. Given these inflation rates are expected to eventually decline, maintaining monetary easing is important to support the economy.

Japan's real consumption is currently stagnant and has remained nearly flat for the past 20 years. Real capital investment is still below that of the first quarter of 2019, before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Clearly, there is limited pressure from domestic demand to drive inflation.

The primary driver of the current high inflation rate is food prices, accounting for 70%, with another 10% attributed to dining out, where the impact of food prices is significant. Other services also show moderate price increases, but these are mainly due to the pass-through effect rather than demand-driven factors.

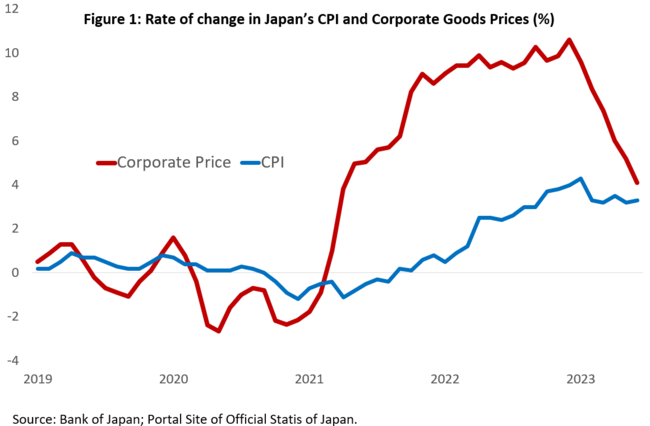

Japan's inflation rate continues to be at a high level because the pass-through effect of the surge in raw material and energy prices since 2021 has not yet subsided. In other words, companies are cautiously and gradually raising retail prices to ease the burden on household consumption, which remains weak (see Figure 1).

Large corporations have increased wages by around 4%, a 30-year high, this year, reflecting spring negotiations. However, wage growth including for small- and medium-sized enterprises, has barely exceeded 2% on average between April and July. Thus, real wages continue to decline. In response to high food prices, consumers are spending less on food and other goods. In addition, the wage increase is primarily a result of labor shortages caused by a declining workforce rather than demand-driven, making it more of a cost-push factor for companies.

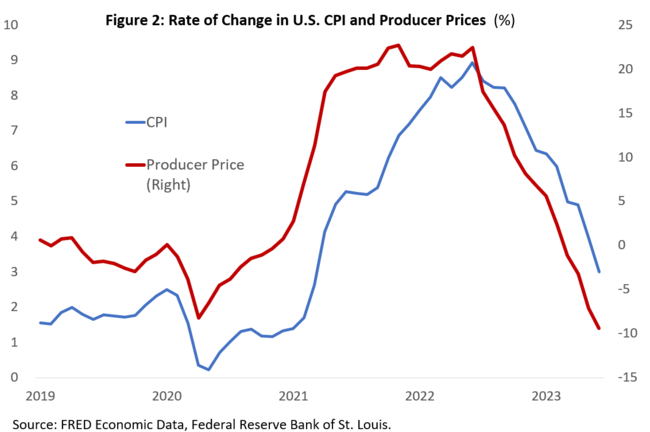

This situation is different from the United States, where inflation driven by expanding demand prevails. In the U.S., the pass-through effect causing cost-push inflation has almost ended since last year. Current inflation is primarily driven by strong domestic demand, especially in the services sector, supported by over 8 million job openings and 4% wage growth. The U.S. inflation dynamics are fundamentally different from Japan's inflation pressures (see Figure 2). This is why the U.S. Federal Reserve raised interest rates rapidly from 0%-0.25% to 5.25%-5.50% within a span of 17 months.

Why the rush?

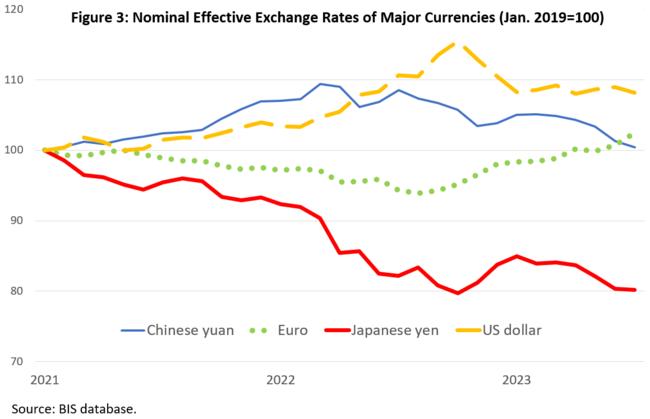

To gauge future inflation trends, it is crucial to examine the movement of food prices. For consumer food prices to rise, there must first be an increase in imported raw material prices, which subsequently leads to corporate price increases. Looking at the contract currency-based corporate prices for food-related products, the rate of increase has already started to decline. However, food-related corporate prices converted to yen have remained high. This difference is primarily due to a significant depreciation of the yen. The yen has depreciated by approximately 13% from the beginning of the year, when the exchange rate was at around 130 yen against the U.S. dollar. There are hardly any currencies among major trading partners that have depreciated to this extent against the yen (see Figure 3). The reason the Chinese yuan has not depreciated as much as the yen, despite the implementation of interest rate cuts, is because China's interest rates are higher. China's 10-year interest rate is 2.6%, which is significantly higher than Japan's 0.6% to 0.7%.

The resurgence of yen depreciation since late May this year can be attributed to BOJ communications that favor the current monetary easing aimed at achieving stable 2% inflation. The unexpectedly robust U.S. economy, coupled with a services inflation rate (excluding energy) in the 6% range driven by strong domestic demand, suggests that there is little likelihood of an interest rate cut in the near term. The Federal Reserve may either raise interest rates once more this year or maintain the current rate until around mid-next year. In these conditions, the BOJ’s insistence on maintaining the status quo could benefit yen carry trades due to the stable interest-rate differential.

Hence, the policy adjustment in July may have been deemed necessary to correct excessive yen depreciation.

Interpreting policy changes

At first glance, the flexibility introduced in the 10-year interest rate adjustments in July might appear modest compared to when the range was expanded to 0.5% from 0.25% last December.

However, in essence, there was a significant shift in policy. This shift can be seen as the practical end of “strongly forming the cap over the yield" that had been put in place with fixed-rate operations in March 2021 when the tolerance for the 0.25% fluctuation band was clarified. In April 2022, a further decision was made that the fix-rate operations would be conducted every working day except when bids were not anticipated. This policy of capping the upper limit was sustained when the fluctuation range was expanded last December.

In contrast, with regard to the July policy adjustment, Ueda explained, “We do not anticipate exceeding 1%, but as a precaution, we set the upper limit at 1%." This suggests that since many estimates of the fair value of the 10-year yield are significantly below 1%, the interest rate is unlikely to approach that level even with the 1% ceiling. In other words, the BOJ reversed its policy of maintaining an upper limit that significantly undercut the fair value in order to pursue robust monetary easing. Moreover, the governor indicated room for further adjustment over the 1% ceiling by pointing out that adjustments exceeding 1% would be considered depending on the economic and price situations at the time. This clearly indicates a deviation from the policy of capping the upper limit. In this sense, it can be said that the July policy adjustment was a step towards normalization, rather than just permitting long-term interest rates to rise above 0.5%.

Given these factors, market economists are currently increasingly expecting that the BOJ will normalize monetary policy by the end of next year, including the end of negative interest rates or the 10-year yield control. It is noticeable that the governor and other BOJ officials have recently started mentioning the possibility of ending negative interest rates in their efforts to correct excessive yen depreciation. This appears to be encouraging market economists hope for further normalization. The bond market is likely to continue exerting upward pressure on 10-year interest rates, testing the BOJ's resolve.

Steps toward normalization

Finally, let's assume that the BOJ has decided to steer toward normalization, temporarily setting aside the agenda of achieving 2% price stability. In this case, one can envision the following sequence for normalization:

First, the central bank could abolish the 0.5% cap on 10-year interest rates and establish a clear range with a 1% fluctuation margin to enhance transparency.

Next, it could examine eliminating the target of 0% for the 10-year yield. This 0% target is no longer binding as the upper limit and the reference rate currently have a more significant impact on the prevailing 10-year yield. However, some market participants may interpret this action as a step toward further normalization, potentially generating further upward pressure on the 10-year yield.

Once the 10-year target is abolished, the next step could be the elimination of negative interest rates applied to part of excess current-account balances, transitioning to 0%. As having both the 10-year interest rate and short-term interest rates at 0% doesn't seem desirable from a yield curve perspective, this sequence is important.

As these steps are taken, it is likely that the 10-year interest rate will become more volatile. Furthermore, in the longer term, considering the future natural interest rate and price trends, the 10-year yield might rise above 1%. This reflects that the natural interest rate is expected to rise due to factors such as corporate green and digital investments, the drawdown of savings associated with the retirement of the baby boomer generation, and fiscal factors. In terms of prices, several factors—such as the increasing need for diversifying production and procurement places due to geopolitical risks causing higher prices, climate change, and wage increases due to labor shortages—will contribute to the likelihood of higher inflation compared to before the COVID-19 crisis.

Therefore, it is necessary for the government and businesses to prepare for a prolonged increase in long-term interest rates. Considering this, it might be more appropriate to postpone the end of the 10-year interest rate fluctuation range a little further into the future.

Lastly, it has already been noted that Japan's inflation has become more susceptible to factors like geopolitical risks, natural disasters due to climate change, and labor shortages due to an aging population, making inflation more likely than in the past. It is worth noting that these factors all contribute to cost-push inflation. Inflation driven by strong consumer demand seems unlikely, given the two-decade-long stagnation, an increasing senior population relying solely on pensions, and the outlook for tax hikes. Therefore, it appears that the BOJ may be facing a phase where flexible monetary policy is required even in the face of cost-push inflation.

Sayuri Shirai is a professor at the Faculty of Policy Management, Keio University, and a former Bank of Japan board member (2011-2016). She holds a Ph.D. in economics from Columbia University. The views expressed here are her own.