Originally published in Japanese on Apr. 22, 2022

Growing uncertainty

The rank-and-file at the Bank of Japan (BOJ) are worried. The term of Governor Haruhiko Kuroda, the former Finance Ministry official who has led the central bank as it implemented unprecedented unconventional monetary policy, will end in April 2023, and power centers in Tokyo are rife with speculation over who will replace him.

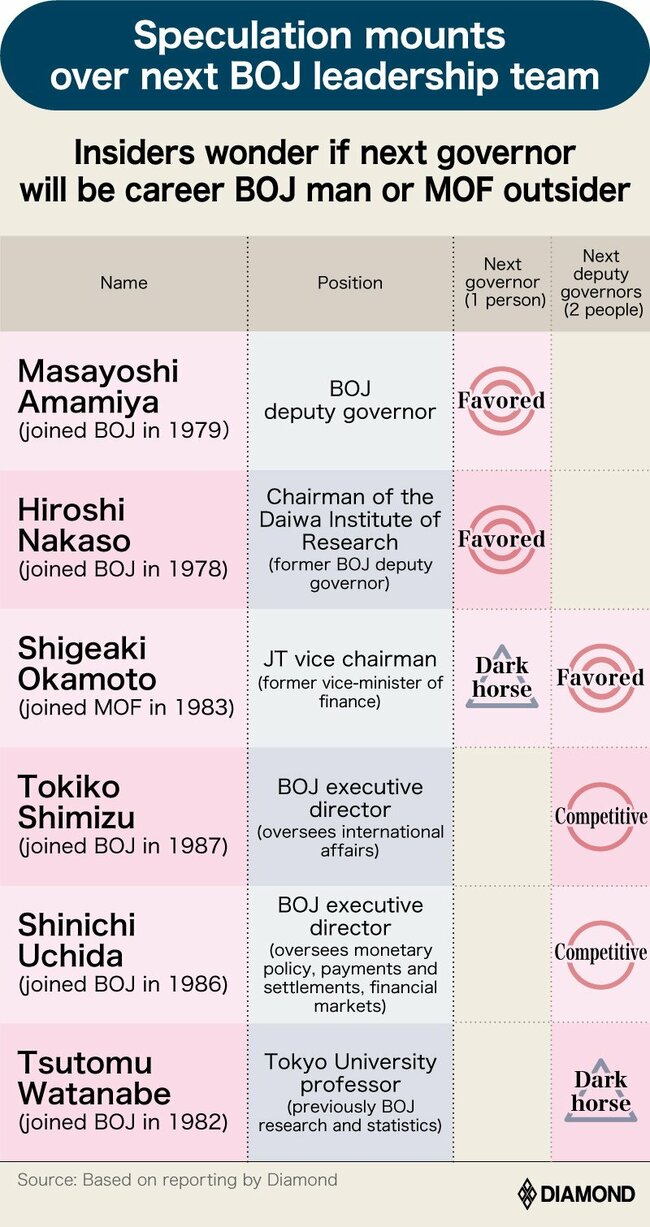

One dark horse candidate has officials at the central bank alarmed: Shigeaki Okamoto, formerly the top bureaucrat at the powerful Ministry of Finance. Most forecasters place Okamoto as a candidate for one of the two deputy governor positions that will become available in March 2023, but some think he could take the top spot. BOJ officials are anxious about a former MOF executive in any leadership position. “[He] would definitely increase uncertainty regarding internal operations,” said a BOJ employee who has worked on monetary policy. Central bank workers suspect that Okamoto may take a more active role in the bank’s daily operations, increasing reporting requirements or demanding more details in otherwise mundane documents.

On top of that, because the BOJ, although legally independent, exists as an entity under the jurisdiction of the Finance Ministry, some worry that business as usual may end under Okamoto and friction could erupt among personnel and organizations.

Trends in Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) have observers looking to Okamoto, now the vice chairperson of Japan Tobacco. Some LDP politicians are keen on Modern Monetary Theory, which posits that the government can pursue fiscal stimulus until inflation picks up, and they want monetary and fiscal policy to act concert. This has the central bank watching the internal working of the ruling party with heightened interest, and it led one former BOJ employee to name Okamoto as a contender for the BOJ’s top spot. Moreover, some believe the Finance Ministry wants one of its own in a leadership position at the central bank, aiming for at least a deputy governor slot.

The impact of the new leadership team could be massive, both for the central bank itself and for Japan’s future economic policy. April 8, 2023, the end of Kuroda’s term, will mark about 10 years since the release of the BOJ’s “bazooka” of monetary easing. Japan is just now starting to experience inflation, but the side effects of this policy — deteriorating profits at financial institutions, lax discipline in controlling government spending and a rapidly weakening yen to name a few — are piling up. Central banks in the U.S. and Europe are moving to normalize monetary policy, but there is no end in sight for easing in Japan, where loose monetary policy is helping to keep the economy afloat. It will be the responsibility of the next governor to find that exit strategy — or to keep pushing forward.

Two other individuals are thought to be the leading Okamoto as candidates to succeed Kuroda: Masayoshi Amamiya, a BOJ deputy governor, and Hiroshi Nakaso, a former BOJ deputy governor and currently the chairman of the Daiwa Research Institute.

Many believe that a pair of March appointments to the Policy Board, the BOJ’s highest decision-making body, indicates that one of the two career central bankers will ascend to the top spot. The government selects appointees for the Board, which are then confirmed by the National Diet. Under the administrations of former Prime Ministers Shinzo Abe and Yoshihide Suga, appointees effectively represented the administration’s monetary policy preferences.

The Board is currently composed of "reflationists" who support aggressive monetary easing and are committed to Kuroda’s policies. They believe that inflation will lead to improved corporate profits and higher wages, in turn boosting consumption and spurring a virtuous cycle in the Japanese economy. But two members, Goushi Kataoka and Hitoshi Suzuki, will step down in June when their terms end. They will be replaced by Hajime Takata, board chairman of the research institute at Okasan Securities, and Naoki Tamura, a senior advisor to Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, respectively. They are the first BOJ Policy Board appointments under Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, and as with Abe and Suga, observers believe the appointments indicate the Kishida government’s preferences.

Neither of the incoming Board members are dedicated reflationists. Kataoka was the most ardent reflationist on the board, but Takata, his successor, is known by market participants to be focused on the bond market. While offering some praise for the reflationary Abenomics program, he distanced himself from the core reflationists by opposing the BOJ’s negative interest rates. He is also close to the Finance Ministry as a long-time member of its main advisory council.

Tamura’s policy leanings are unclear, but he comes from Japan’s megabanks. He will likely pay close attention to the side effects of monetary easing like the worsening profits at financial institutions. “They’re moderate, but the government chose individuals who think that the ultra-easy policy needs to be modified,” said Ryutaro Kono, chief economist at BNP Paribas Securities.

In other words, the new appointments will make the Policy Board “more orthodox compared to during the previous administrations, which chose only reflationists,” said Hideo Hayakawa, senior fellow at the Tokyo Foundation for Policy Research and a former BOJ executive director. They also hint that the next governor, as well as the new deputy governors, will be career BOJ officials with more conventional monetary views, he added.

Amamiya has spent his entire career at the BOJ, and he helped implement Kuroda’s policies as the executive director in charge of monetary policy at the central bank. However, neither he nor Nakaso, another long-time BOJ man, is committed to reflation. Additionally, many within the BOJ want a career central banker to follow Kuroda, who originally came from the Finance Ministry. Between the fact that the two seem to share the Kishida administration’s preference for more conventional monetary policy and the desires of BOJ officials, most believe they are the leading candidates to become the next governor.

Which among them is in a stronger position is a matter of debate, and likely to be affected by events over the next year. One former BOJ official noted that developments like an undesirable weakening of the yen could lead to stronger criticism of the central bank. “I had originally thought it was 60% Amamiya, 40% Nakaso,” they said. “Now I think it’s the opposite, because thinking about the perspective of continuity of monetary policy, it’s a negative [for current Deputy Governor Amamiya].”

The Finance Ministry’s Okamoto is also in the running, and market participants have for some time called for Asian Development Bank President Masatsugu Asakawa, another former Finance Ministry official, to head the BOJ. However, Asakawa’s career path closely matches that of Kuroda, and most of those familiar with the situation believe the Policy Board appointments mean he is unlikely to get the nod this time.

The BOJ governor is assisted by two deputy governors, both of whom will see their terms end in March 2023. Two names have been floated as possible candidates, both long-time employees at the BOJ.

Shinichi Uchida has worked on monetary policy since 2012, including five years as the head of the Monetary Affairs Department. He worked on many of the unconventional monetary policies under Kuroda and is considered one of the most capable officials in the BOJ. He has been an executive director since 2018 and was reconfirmed to his position in April. Some believe he will be promoted to deputy governor to become the “next, next candidate for governor,” according to one former BOJ official.

Tokiko Shimizu became the head of the BOJ’s Takamatsu Branch in 2010, rising to become the first woman to serve on the Policy Board in 2020. She has been one of the foremost professional women at the central bank. With the government calling for more female advancement in the workplace, the chances of a female deputy governor have increased.

Another possibility exists in Tsutomu Watanabe, a professor at the University of Tokyo Graduate School and a former BOJ official. He is a leading expert on price research and a potential, albeit unlikely, deputy governor. “He is a few years younger than Amamiya and Nakaso, and it makes sense looking at the governorship based on seniority,” said one former BOJ employee, indicating that the deputy governor should be junior to the governor. Although this speculation is based on the Japanese employment system in which professional advancement is based on seniority, the year officials joined the central bank is in fact often an important factor in considering promotions and appointments.

Political turbulence

The main variable that could disrupt an otherwise smooth appointment process is the upper-house election that will come in July. While many expect the LDP to perform well, the Kishida administration faces significant electoral headwinds in the COVID-19 pandemic and inflationary pressure. Moreover, Kishida’s rivals within the party are moving. There are whispers in Nagatacho, the center of Japanese politics, that the LDP’s reflationists will gain more influence over the BOJ appointments if the party fares poorly in the summer election.

The leader of these reflationists is none other than former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe. Despite Kishida’s efforts at reconciliation, the LDP is split between Abenomics-supporting reflationists who favor greater government spending and fiscal hawks. Abe gave a speech at the inaugural meeting of the Caucus for the Promotion of Responsible and Proactive Fiscal Policy, a new parliamentary group launched in February that supports more active fiscal policy. With the yen falling to historic lows in part because of the BOJ’s easing, on April 25 Abe gave another speech at a Diet group focused on post-COVID economic policies in which he supported the BOJ’s stance on easing, saying there was no “absolutely no need” to be worried about the specific level of the yen. As the head of the LDP’s largest intra-party faction and an elder statesman, Abe is still widely viewed as a kingmaker within the party and his monetary policy preferences are clear.

On top of that, rumors are also circulating that former Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, former Secretary-General Toshihiro Nikai and others have joined together in an all-out intra-party struggle against Kishida ahead of the upper-house election. The politicians in this coalition are not reflationists, but they see Kishida as weaker than Abe, and ousting him would improve their own standing within the LDP. These factional struggles could further weigh on the LDP’s performance in the election and sap Kishida’s ability to choose his own appointees.

One informed observer even speculated that if Kishida loses his hold over the party in the upper-house election, Etsuro Honda, the former ambassador to Switzerland and a member of the "ultra-reflationist" camp who helped direct economic policy as an advisor to the Abe administration, may become a candidate for the BOJ governorship.

However, the consensus in Tokyo views such scenarios as unlikely. Based on the recent Policy Board appointments, “the chances are high that the next BOJ head will be someone who is not a reflationist,” said a market participant.

Small steps

Whoever succeeds Kuroda as head of the BOJ, their options may be limited. Wages have not risen in Japan, and underlying economic growth remains subdued, so observers do not expect a sustained rise in interest rates to come soon. BNP Paribas Securities’ Kono expects around late 2023 the central bank will end negative interest rates and raise the 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yield target from the current 0%-0.25%.

At its April 28 Monetary Policy Meeting, the BOJ held fast to its current easing program. Even as the yen sank to a 20-year low against the dollar, the bank showed clearly that it was more focused on curbing rising interest rates than stopping the yen’s slide. Following the meeting, most believe that a major policy shift under the current leadership is unlikely. As a result, the leadership from next spring is expected to take modest steps toward normalization, such as ending negative interest rates and slightly increasing the 10-year JGB yield target.

Put differently, these steps may be the limits of what is possible in the next governor’s 5-year term. Like the government, the BOJ is currently tied up dealing with immediate issues, so discussions within the bank about an exit policy have languished.

Markets, however, expect the new leadership to provide detailed explanations about its big-picture policies that will account for complexities like rising interest rates in the exit from unconventional easing. Whether the next governor is a career central banker or a former government official, daunting challenges lie before them.

(Originally written in Japanese by Kohei Takeda, translated and edited by Connor Cislo)