Originally published in Japanese on May. 5, 2022

Historic slide

The yen reached about 130 per U.S. dollar on April 28, a roughly 20-year record, as hawkish comments from central bankers in the U.S. drove yields on the 10-year U.S. Treasury note toward 3%. With the European Central Bank also hinting at an interest rate hike before the end of the year, the euro is strengthening against the yen. The Japanese currency has weakened more than any of its major peers.

While major central banks overseas are moving to raise interest rates, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) is sticking to its policy of monetary easing. Many view this as the biggest factor behind the drop in the yen. The growing view that the weaker yen will hit Japanese households’ purchasing power has led some to call for the BOJ to rethink its loose monetary policy and prevent a “bad weak yen.”

BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda has maintained that “a weaker yen has more positive [than negative] effects on the Japanese economy,” and Japan’s central bank has continued its unlimited fixed-rate operations to buy Japanese government bonds (JGBs) to keep 10-year yields within the upper limit of 0.25%. Pressure to act is now growing on the BOJ.

However, the yen’s depreciation will not stop, even if the BOJ raises interest rates.

Interest rate increases in the U.S. make assets there more attractive for institutional investors in Japan, leading to more outbound investment. Institutions sell yen to buy foreign exchange they can use for that spending. In this sense, Japan’s low long-term interest rates factor into the yen’s depreciation, because Japanese assets offer relatively little return compared to those overseas.

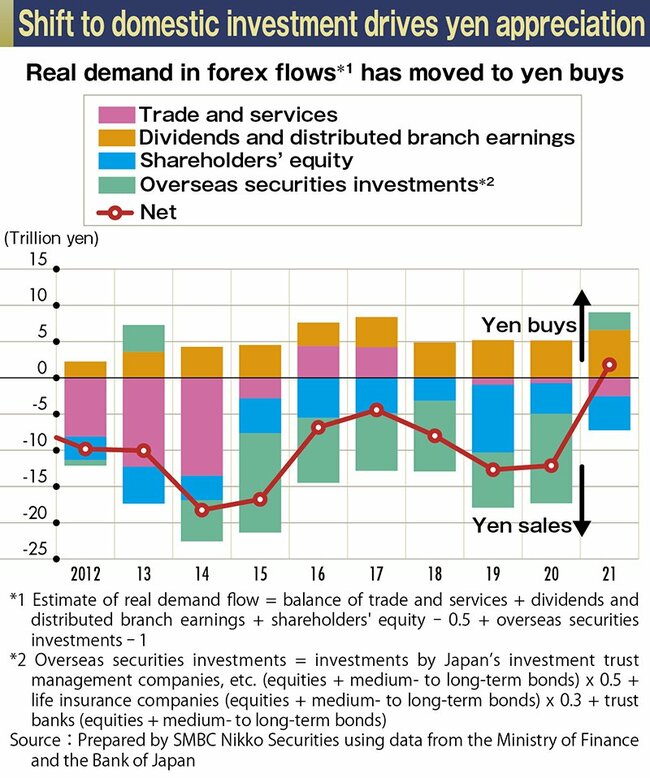

However, 2021 trends in the investment in overseas securities (investment in securities that affects the real demand for dollars and yen as calculated by SMBC Nikko Securities) actually worked to strengthen the yen. This was largely due to portfolio rebalancing by public pension funds like the Government Pension Investment Fund, in which they sold assets denominated in foreign currencies and replaced them with yen-denominated assets.

A similar trend is expected in 2022. When asked about their investment plans for the current fiscal year, many institutional investors like life insurers said they will increase their holdings of long-term Japanese government bonds, which have had rising yields.

At least presently, it is thus difficult to say that the yen’s depreciation is being driven by an increase in overseas securities investment. That means there is no need for the BOJ to rush to raise interest rates or otherwise curtail its easing program.

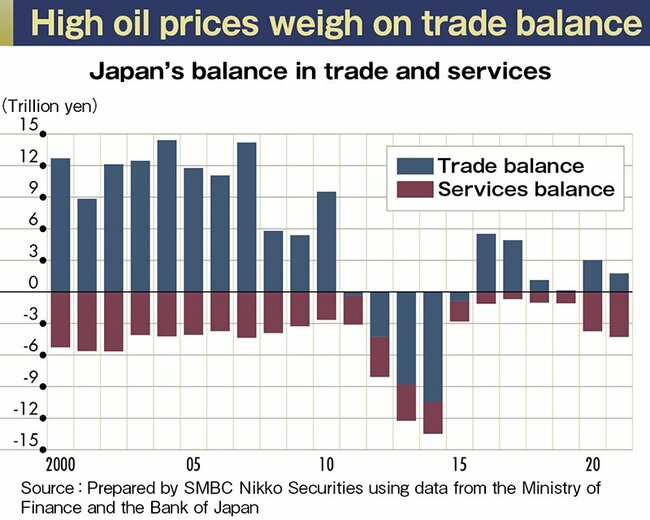

Looking at the composition of real demand in the foreign exchange market, Japan’s growing trade deficit resulting from higher oil prices is more likely to be the main driver of the yen’s depreciation.

The question then becomes one of how best to avoid the adverse effects of a trade deficit when faced with a prolonged period of high oil prices. This becomes doubly important when considering the impact of high oil prices on Japanese households. Both of these matters, however, are the purview of the Japanese government, not the BOJ.

The government and ruling coalition have indeed decided to enact a supplementary budget in fiscal 2022. As a measure to address the high oil prices, it has been suggested that this budget increase the subsidies to oil wholesalers to 35 yen ($0.27 at current exchange rates) per liter from 25 yen. This would be done to keep the average national gasoline price around 168 yen per liter (the current standard price is 172 yen per liter).

However, holding down gas prices through government spending will not lead to a reduction in Japan’s trade deficit, and the country’s terms of trade will continue to worsen. If the yen continues to weaken as a result of that, households will see their purchasing power further decline.

Rate hike risks

Fundamental changes are needed in Japan’s balance of payments, and the adverse effects of the trade deficit will likely continue to buffet the country unless the volume of crude oil imports falls. Changes in energy policy, including the restart of nuclear reactors, are necessary. However, many are opposed to this proposition, and little progress is likely ahead of the upper house election this summer.

The government could enact policies to promote exports. This would take advantage of the weak yen while also improving Japan’s trade balance.

Growing exports is not a simple matter. The extremely strong yen in 2011 (75 yen per dollar) led many manufacturers to move the production bases overseas. Furthermore, labor shortages are a concern because of Japan’s declining working-age population. Given these structural issues, companies are unlikely to make significant capital investments in Japan.

But while policymakers will find it challenging to increase goods exports, they could likely find more success in lifting Japan’s exports of services. The best policy to improve Japan’s balance of payments in this way would be to promote more inbound tourism.

Before that, however, the general thinking in Japan needs to change. There is little drive to restart the economy amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Many were concerned about the infections that spread during the string of holidays in early May, when many people traveled throughout the country. Enacting policies that would draw more tourists to Japan will be difficult as long as these circumstances prevail.

The sharp rise in crude oil prices triggered by the crisis in Ukraine is the biggest factor behind the yen's depreciation, and these high prices are likely to last for some time. Japan needs a whole-government effort to stop the yen from further weakening, but currently, the authorities do not seem particularly alarmed, and the BOJ is the main institution under fire.

Would the yen’s slide stop or slow if the BOJ raised interest rates? If investors can be incentivized to shift their funds to yen-denominated bonds instead of overseas investments, upward pressure on the yen would grow. However, a slight increase in negative short-term interest rates is not expected to be enough to trigger such a change.

Such a shift would require the gap between long-term interest rates in the U.S. and Japan to narrow significantly. One possibility would be to end the BOJ’s yield-curve control, which keeps the 10-year JGB yield pegged at or below 0.25%. However, rising long-term interest rates would also considerably increase the financing costs of Japanese households and businesses.

The BOJ has kept long- and short-term interest rates low not to keep the yen from appreciating, but to boost private-sector demand for funds even as the equilibrium real interest rate falls. If long-term interest rates were to rise now, households and businesses would lose any appetite for borrowing, leading to a greater economic slowdown.

With few available measures to address its declining birthrate and aging population, economic growth in Japan is expected to remain subdued. That means outward investment by companies will further pick up, accelerating capital flight and the depreciation of the yen.

Ultimately, the biggest issue is that Japan’s potential growth rate is so low that the BOJ has no choice but to continue its negative interest rate policy. Unless the country develops a growth strategy to deal with this, the yen will continue to weaken regardless of any other measures.

Makoto Noji is the chief foreign exchange and foreign bond strategist at SMBC Nikko Securities. He graduated from the Faculty of Law at Keio University in 1993 and joined Fuji Bank in 1996. He also worked at Fuji Securities, JP Morgan Securities, Credit Suisse First Boston Securities, Shinko Securities, and Mizuho Securities before joining Nikko Cordial Securities (now SMBC Nikko Securities) in 2011 as a senior fixed income and foreign exchange strategist. He has held his current position since April 2017. The views expressed here are his own.