Inflation, the BOJ, and the yen

Online and in-person conversations with foreign clients during two overseas marketing trips in June, the first since late 2019, were great opportunities to learn what market participants want to know about Japan. The main topics were three related items: inflation, Bank of Japan (BOJ) policy, and the outlook for the yen.

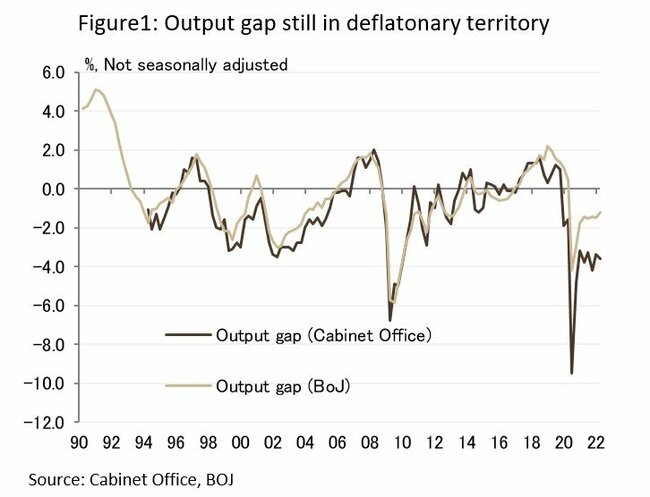

Our view is that Japan's current 2% to 2.5% year-on-year CPI inflation is unsustainable beyond next year unless international energy prices continue to rise meaningfully. There are three reasons for this: 1) Japan has a negative output gap because of the sluggish recovery from the pandemic (Figure 1); 2) persistently low, if not zero, inflation expectations; and 3) low wage inflation (see below for more details).

Accordingly, the BOJ is unlikely to tighten policy for the foreseeable future, despite the sharp yen depreciation. The governor who follows incumbent Haruhiko Kuroda, who ends his second five-year term in April next year (in our call, either current Deputy Governor Masayoshi Amamiya or former deputy governor Hiroshi Nakaso), will not rush to start policy normalization.

On the yen, it is hard to see a reason for appreciation from the Japanese side, and we would not be surprised to see further depreciation in summer. At the same time, we argue that the outlook for the dollar-yen in the coming years mainly depends on U.S. monetary policy and the long-term yield, not the BOJ or Japanese policy. Given that our colleagues expect policy rate hikes to stop at the end of this year, our FX strategist expects the dollar-yen to return to 125 yen per dollar from the current 135-140 by then.

Inflation fundamentals

Our outlook for inflation and BOJ policy is in line with the consensus view among Japanese BOJ watchers and many market participants, but there is some pushback to this view from foreign investors. They, especially macro investors, believe central bankers' reaction function has shifted globally toward preventing high inflation rather than stabilizing the economy, and that change applies to the BOJ as well, especially in the face of criticism over the yen’s drop from the public and politicians. They remember what happened in the U.S. and Europe last year when the Federal Reserve Board and European Central Bank said that high inflation was transitory during spring, and they think that the BOJ is also making the same mistake with a year lag.

We disagree. Japan's inflation dynamics are very different from the rest of the world, so the difference in central bank behavior is warranted. Elsewhere, higher import prices are largely passed through to consumers, and consumers require higher wages to protect their purchasing power, which causes higher domestic inflation (the so-called “second-round effect”).

However, Japanese businesses are reluctant to pass the higher import costs to consumers, as they would lose market share. Many consumers, especially younger ones, have no experience with sustained increases in prices (i.e., they have low or no inflation expectations), and they will not accept higher prices.

Some goods, especially energy and foods, tend to have greater pass through to consumers, which raises headline CPI inflation. However, since many businesses are squeezed at the margin, they cannot raise wages. Workers accept this, as their priority is job security under Japan’s unique system of lifetime employment, seniority-based wages, and in-house labor unions.

To be sure, this system is gradually fading and basically applies only to full-time workers at large firms. Still, this system broadly defines the customs of employment practices, even among small and medium firms.

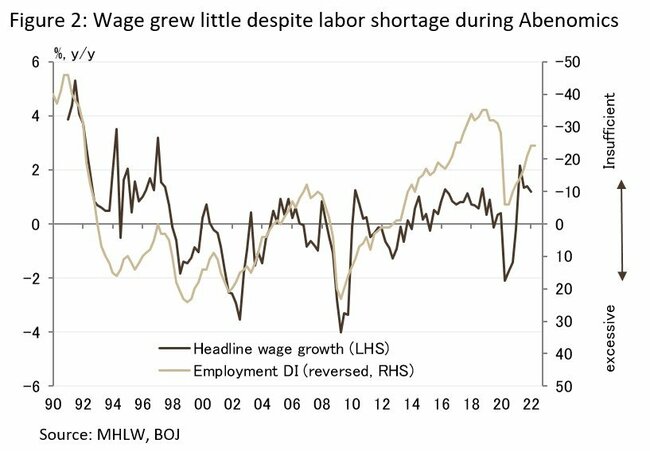

In any event, the lack of strong demands for wage hikes from workers despite higher inflation — which is the second-round effect on domestic prices from higher import prices — should serve as proof of the differences in Japan’s inflation dynamics. Wage inflation has been very stable despite an increase in firms’ perception of a labor shortage (Figure 2).

Some argue that the sharp yen depreciation, which raises the import prices of energy and foods, will upset the public, so political pressure will prompt the BOJ to address the depreciating currency by tightening policy. However, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida shares Kuroda’s assessment on the issue: Higher inflation in Japan is mainly due to a surge in international commodity prices, not the depreciation of the yen.

Criticism comes from the opposition parties, which claim the current inflation is "Kishida inflation." Higher prices are a key reason for a recent fall in the approval rate of Kishida's administration (down from a peak at 59% in early June to 50% on June 24-27, according to a poll by national broadcaster NHK), but a survey of 545 (517 responses) candidates in the July 10 upper house election by NHK showed 48% of respondents said the BOJ should "maintain aggressive monetary easing" while 24% (mainly those from opposition parties) said the central bank "should turn to tighten monetary policy."

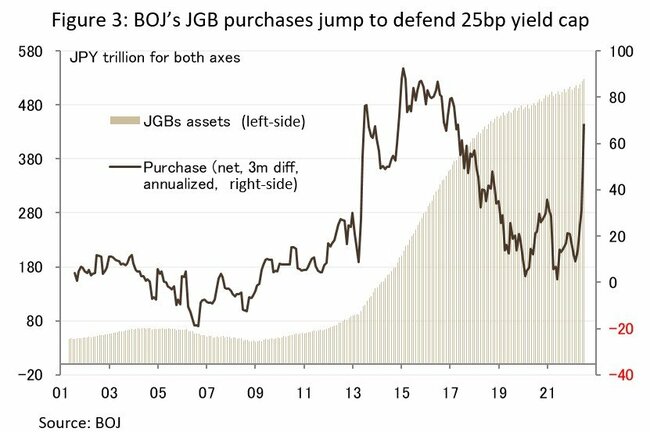

Moreover, some argue that an increase in bond purchases to defend the 0.25% yield cap on 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) is a problem (Figure 3). However, we do not think that is the case. The pressure on the BOJ to buy bonds will not continue indefinitely unless the U.S. long-term yield continues to rise despite concerns about a coming U.S. recession.

In sum, we argue that Japan will not change while the rest of the world struggles to fight the kind of high inflation that has not been observed in the last 40 years.

The stability of Japan’s inflation dynamics may appear welcome for the time being, but no domestic inflation also means little energy for growth among Japanese businesses and households in our view. Amid secular challenges posed by demographics (a shrinking and aging society), extremely high government debt, and low productivity growth with low levels of investment and a rigid labor system, Japan’s economic and social structure needs to decisively change to avoid secular contraction.

We hope the government and private sector, especially large firms, will pursue comprehensive reforms with a sense of crisis while the BOJ buys time to ease the pain of these reforms. Without these aggressive changes, we think the interest in Japan among overseas investors and the Japanese themselves will soon fade, especially after the current transition period from the old normal (pre-pandemic and pre-Ukraine invasion) to a new normal with no clear guidance.

Masamichi (Masa) Adachi joined UBS Global Research in October 2019 as Chief Economist for Japan. He started his career at the Bank of Japan in 1991, where he mainly analyzed business conditions and conducted financial & economic research in both the Research and Statistics Department and the Financial Markets Department. He joined JP Morgan as Senior Economist in October 2006, where he was responsible for researching, analyzing, and providing commentary on the global economy and financial markets, with a primary focus on Japan. The views expressed here are his own.