BOJ still on course

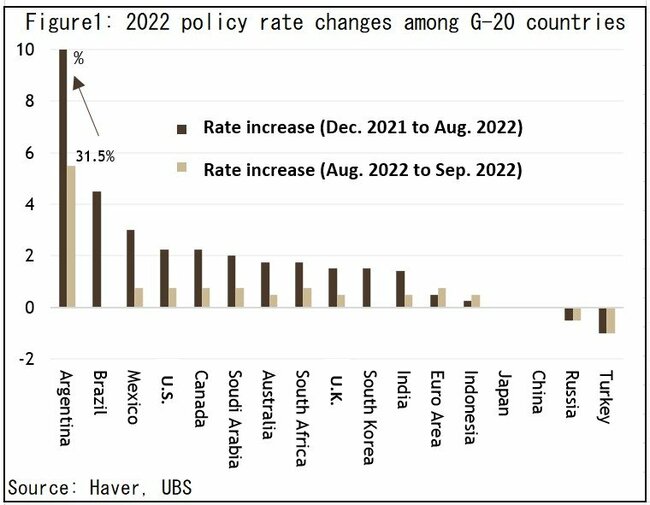

Policy developments over the last couple of months, especially in September, were as we expected (except for the U.K.’s mini-budget and the Bank of England’s sudden gilt purchases). Almost all central banks continued to rapidly tighten monetary policy to stem excessive inflation and prevent a rise in inflation expectations among the general public. Among the Group of 20 countries, all central banks except those of Turkey, Russia, China, and Japan, raised policy rates this year and in September (Figure 1).

The U.S. Federal Reserve raised its policy rate by 75-basis-points to 3% to 3.25% on September 21. It also updated the Summary of Economic Projection at the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC). The pace of rate hikes was in line with market expectations, but the projection looked more hawkish than expected, showing a further 125-basis-point rate hike to 4.25% to 4.5% at the end of this year and one more 25-basis-point hike to 4.5% to 4.75% in 2023 as the median projection of FOMC members. Of course, this projection may shift in either direction based on economic and inflation developments. However, strong remarks from FOMC Chair Jerome Powell at the press conference after the meeting underscored how important it is to stem high inflation, suggesting that the FOMC needs to confirm a slowdown in inflation before it will ease its hawkish stance. This hawkish stance creates further pressure for the U.S. dollar to appreciate.

Amid this global tightening, the Bank of Japan (BOJ) stuck to its aggressive easing with yield-curve control on September 22. That means Japan’s policy rate is -0.1%, and 10-year Japanese government bond (JGB) yields are capped at 0.25%. BOJ watchers were in agreement that no policy change would come at the meeting; all 49 respondents to Bloomberg’s survey expected no policy change. However, Governor Haruhiko Kuroda’s message during a press conference that the Bank has no intention to tighten policy in the next two to three years prompted the yen to rise to nearly 147 against the dollar from below 145.

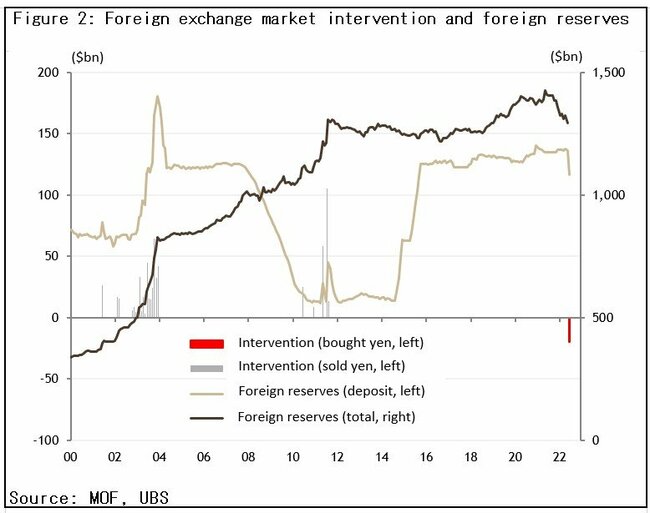

After the press conference, the Ministry of Finance (MOF) decided to intervene in foreign exchange markets by buying yen and selling U.S. dollars from its foreign reserves, the first such intervention in 24 years (Figure 2). Data released on September 30 showed MOF bought 2.8 trillion yen, using 1.5% of total foreign reserves. The yen briefly fell to 140 against the dollar but quickly snapped back to about 145 within a week. Still, we think this was successful in stopping the yen’s depreciation as U.S. yields unexpectedly rose to 4.0% that week. We expect MOF to intervene again if necessary.

One may anticipate the BOJ to follow by raising its yield-curve control range or implementing any kind of policy tightening, based on the assumption that the public and the government are upset by the higher living costs that come with the yen’s depreciation. The sharp rise in yields for JGBs with maturities longer than 10 years and a jump in the BOJ's bond purchases underscore the pressure from markets. We think this market view that the BOJ will eventually tighten policy will not vanish, as many international investors believe that Japan’s inflation will follow the global pattern, forcing the BOJ to move in the same direction. This speculation is likely to intensify as the end of Governor Kuroda’s term (April 2023) draws near.

However, we believe the BOJ will not change policy, despite this pressure, for three reasons. First, the BOJ and we expect that core consumer price index (CPI) inflation (which includes energy but excludes fresh food) will slow to below 2% year-on-year in fiscal 2023, although monthly inflation is likely to accelerate to 3.3% or higher until early 2023 from 2.8% in August. Worth noting is that a U.S.-style core measure, which excludes all food and energy, rose only 0.7%, with service prices rising merely 0.2% in August. Unless imported energy and food prices rise again during the next year, we find it hard to expect CPI inflation higher than 2% will continue in Japan. Second, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has said he has no intention to give up on Abenomics’ 2% inflation target, as he does not oppose the economic program. Finally, UBS expects no more rate hikes from the Fed in 2023 (and three cuts from September), which would weaken the dollar. Given that the current yen deprecation against the dollar is mainly driven by the dollar’s appreciation, the BOJ should not move now, in our view, as the Fed’s pivot from a hawkish to less hawkish, or even dovish, the stance will probably change the trend of the currency.

Small steps

How then will Japanese policymakers counter the higher living costs and yen depreciation in the immediate future? In short, Japan's policy mix is a combination of easy monetary policy aimed at sustaining a high-pressure economy that creates domestic demand-driven inflation, modest fiscal support for partially offsetting higher energy and food prices, and foreign-exchange market intervention to counter the rapid currency movements.

Some argue that the combination of continued monetary easing and foreign-exchange market intervention is a contradiction, and the BOJ should be flexible in raising policy rates. We disagree. It is true that if Japanese policymakers aim to change the trend of the yen from depreciation to appreciation (or target a certain level) and use intervention as a tool, monetary policy must also tighten. But that is not their objective. We think the combination of easy monetary policy and intervention through yen purchases is right in the current circumstances since we believe the main reason for the yen’s depreciation is the dollar’s appreciation, which, as noted above, we believe will eventually change.

Moreover, if the interest rate differential is the main reason for the yen’s depreciation, the BOJ would need to raise rates aggressively, which we believe would be unacceptable given the weakness in domestic demand and high government debt. Small rate hikes are probably not enough to stop the yen’s trend, as suggested by the Korean case. Indeed, Korea has raised policy rates by 175 basis points this year from 1.0% (initially 0.5% from July 2021) to 3.0%, but the won depreciated 20% against the dollar since the end of last year (the yen depreciated 27%).

In our view, a better approach to the weakening yen could be encouraging exports and opening up to inbound tourists. From this perspective, the government’s decision to lift border restrictions and accept foreign tourists from October 11 is welcome. Kishida mentioned in his October 3 policy statement on the first day of an extraordinary Diet session that the government will target over 5 trillion yen, 1% of gross domestic product, in consumer spending by foreign visitors. That is close to the record in 2019. We do not think this will immediately impact lowering the pressure on the yen to depreciate, and the target looks overly aggressive given that half of the visitors in 2019 were Chinese who are now under zero-COVID policy travel guidelines.

Still, reopening Japan is a step in the right direction. In addition, the government is now encouraging firms to invest in Japan to reestablish supply chains for national economic security. The current weak yen should boost the appeal of this policy initiative.

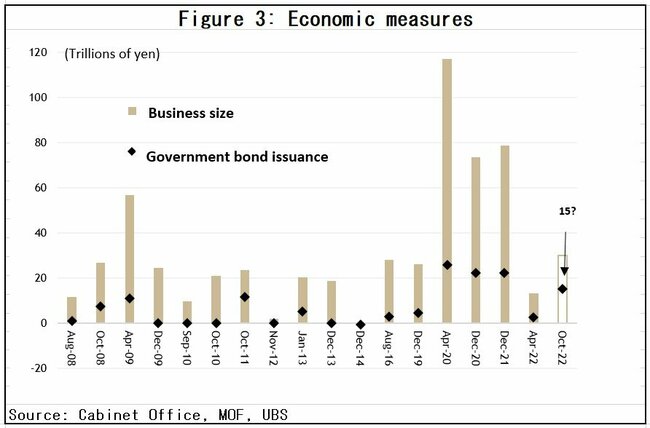

The government will form a second supplementary budget during this extraordinary Diet session, which is scheduled to end on December 10. In his statement, Kishida said the fiscal package would address three areas: higher prices (living costs) and the yen’s depreciation, structural wage hikes, and investment and reforms for growth. The government is considering capping price hikes of electricity bills from next spring. Details about the measures and the total size of the budget are still unknown, but we guess about 15 trillion yen (3% of GDP) in new bonds (i.e., new fiscal deficit) will be issued, close to the latest estimate of the output gap while the government’s headline number of the measures that include private spending(so-called “business size”)could be much larger.

Compared to the U.K., where the combination of monetary tightening and fiscal expansion with the “mini-budget” became the source of market turmoil, Japan has no apparent policy-mix conflict with a spending package. Indeed, monetary policy is not tightening because persistently high inflation is not a concern for Japan. Moreover, the size of the extra budget is not particularly large compared to those of the last two years (Figure 3). We thus think the announcement of the budget will not surprise financial markets. At the same time, however, it probably will not significantly impact the growth outlook.

Of course, the size of the budget (more specifically, the issuance of new JGBs) could be much larger than our expectation. In that case, market pressure to sell JGBs, yen, and Japanese risk assets, such as equities and properties, may rise. However, we think the government, especially MOF, is aware of this risk, and Kishida will listen to their warnings.

Masamichi (Masa) Adachi joined UBS Global Research in October 2019 as Chief Economist for Japan. He started his career at the Bank of Japan in 1991, where he mainly analyzed business conditions and conducted financial & economic research in both the Research and Statistics Department and the Financial Markets Department. He joined JP Morgan as Senior Economist in October 2006, where he was responsible for researching, analyzing, and providing commentary on the global economy and financial markets, with a primary focus on Japan. The views expressed here are his own.