Originally published in Japanese on Sep. 20, 2022

New lows

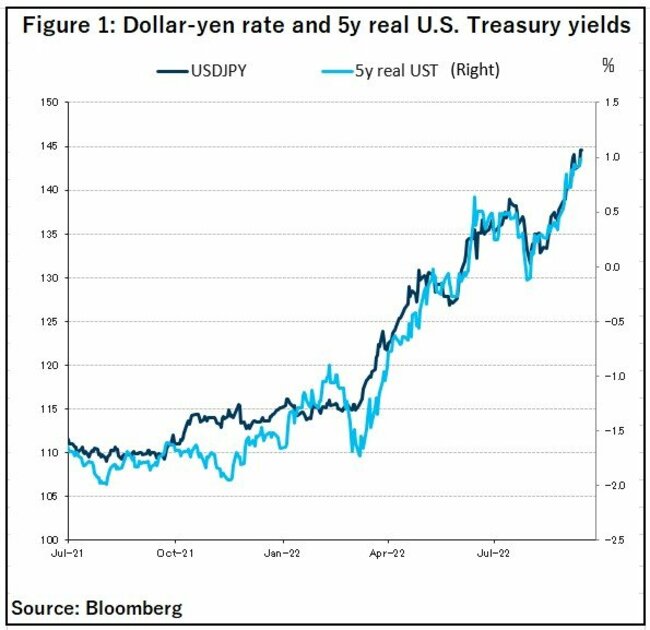

The dollar-yen's sharp rally can be explained mostly by the ongoing upward trend in 5-year real U.S. Treasury yields, which reflects the repricing of the U.S. Federal Reserve's terminal rate and positive U.S. data surprises (Figure 1). Fed funds future markets’ pricing of the Fed’s terminal rate rose to 4.5% from around 3.2% in early August on the back of recessionary concerns, with the upside surprise in August consumer price index (CPI) readings and comments by Fed Governor Jerome Powell and other officials emphasizing the need for hawkish policies to dampen demand and prevent heightened inflation from becoming entrenched. Additionally, U.S. economic data are beating market expectations, tempering fears of an imminent recession that prevailed over the summer.

At the same time, Japan's idiosyncratic factors are no longer causing the yen's descent, in contrast to earlier in the year, when the Bank of Japan’s (BOJ) relatively dovish stance and the negative terms-of-trade shock from higher commodity prices drove the yen’s underperformance. Markets are already well aware of the BOJ's ongoing dovish stance, reconfirmed by Governor Haruhiko Kuroda at the past few monetary policy meetings.

Additionally, declines in commodity prices since the summer are set to reverse the negative terms-of-trade shock seen earlier in the year.

Jawboning limits

The rapid yen depreciation has drawn escalating verbal interventions from Japanese officials. Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki noted on Sept. 7 that he is "concerned about the one-sided moves in the yen" and "will take action as needed," while Chief Cabinet Secretary Hirokazu Matsuno on the same day said that Japan will "need to take necessary action if these moves continue." A trilateral meeting was held by the Ministry of Finance (MOF), BOJ, and Financial Services Agency, after which MOF Vice Minister of Finance for International Affairs — Japan’s top currency official — Masato Kanda noted that the government is ready to take the necessary response in the foreign exchange market. A meeting between Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and Kuroda further fueled concerns about intervention risks.

These statements and meetings signal movement toward actual intervention. The August 1998 high of 147.6 yen has become a natural point of focus, as MOF used to buy yen around the 130-140 range in the 1990s. However, the effectiveness of any intervention will be in doubt if the U.S., faced with its own inflation problem, does not agree to joint action, a position the U.S. Treasury reconfirmed on Sept. 7. While intervention could provide temporary upward pressure on the yen, continued U.S.-Japan monetary policy divergence, the fundamental driver of the yen’s decline against the dollar, would likely render such effects short-lived at best, and would not determine the medium-term direction of the dollar-yen exchange rate, in our view.

A strong dollar

This ultimately leaves the dollar-yen’s fate in the hands of the Fed. We expect the Fed to hike its policy rate by another 75 basis points at this week’s Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) as U.S. inflation remains elevated, as confirmed by the August CPI.

Looking ahead, while inflation and Fed pricing could remain volatile and pose further upside risks to the dollar-yen rate in the near term, these risks may ease as inflation diminishes. Changes in consumer demand away from goods, a stronger dollar, a drop in commodity prices, the restocking of inventories, and the easing of supply chain pressures should all add up to a more measured set of increases in core goods prices.

Furthermore, private rent measures are consistent with our view that rent inflation may slow from recent readings. A low inflation result for September could anchor terminal rate expectations around 4%. A 75-basis-point rate hike at the September meeting could bring the Federal funds target range into a restrictive range (that is considered to slow the economy and inflation) relative to the FOMC members’ assessment of a long-term neutral policy rate of 2.5% and closer to their terminal rate. This would suggest a slower pace of hikes in the coming quarters.

While the dollar-yen could see further upward momentum in the very near term if U.S. inflation continues to surprise to the upside (with the 1998 high of 147s as the next key technical level), we see the currency pair trending downward in the medium-term. We forecast the yen to end this year around 140 versus the dollar and to decline toward 130 by the second half of next year.

First, the eventual peaking of U.S. inflation and slowing global growth may start to weigh on Fed hike expectations that are already marked up to 4%, with a potential shift to rate cuts to reduce the scope of restrictiveness in rates. Second, Japan’s balance of payments is likely to improve as commodity prices drop and borders gradually reopen. Third, the selection of the next BOJ Governor over the winter (Kuroda’s term will expire in April 2023) may reinvigorate the discussion of future BOJ policy changes and exert some upward pressure on the yen. Downside risks to our dollar-yen forecasts may intensify if the market focus shifts from global inflation pressures to growth concerns.

While dollar-yen topside may start to fade over the coming year, exchange rates are unlikely to quickly revert to pre-2022 levels. The dollar’s strength since early 2022 is not only vis-a-vis the yen, but almost all major currencies. The broad dollar rally was largely due to three shocks: 1) a tightening of financial conditions by the Fed; 2) risks to European growth from surging natural gas prices; and 3) repercussions from China’s deleveraging and zero-COVID policies. Differentiated terms-of-trade from rising commodity prices have also sorted out the relative winners and losers (e.g., the yen). For the dollar to turn, a growth rebound outside the U.S. is necessary, along with a dovish turn by the Fed.

Shinichiro (Shin) Kadota is the FX Strategist at Barclays in Tokyo. Shin joined Barclays in 2008 and has worked in various teams covering Japanese banks, foreign bond investment for institutional investors, foreign exchange, and yen-rates markets. He graduated from UCLA in 2008 with a degree in International Economics.