Originally published in Japanese on Oct. 6, 2022

Defeat and recovery

It was a historic defeat for NEC.

Six years ago, the company failed to win a contract for the trans-Pacific cable “Jupiter,” which connects Japan, the U.S., and the Philippines. The project was completed in 2020.

More submarine cables extend across seabeds every year, enabling massive amounts of data to flow around the world. There are 530 cables in 2022, including those currently in the planning phase. According to TeleGeography, a U.S.-based research company, their total length exceeds 1.3 million kilometers.

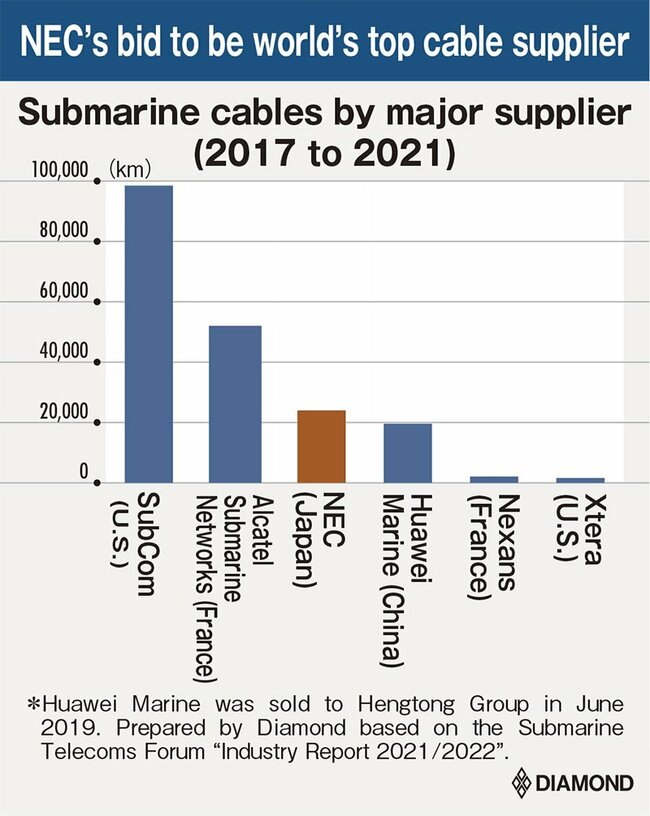

Only a limited number of companies can manufacture and lay the delicate cables that run for thousands of kilometers. The cables need to operate stably for 25 years at depths of up to 8,000 meters. NEC has supplied 300,000 kilometers of cable, enough to circle the globe 7.5 times. It is one of the world’s top undersea cable companies, along with SubCom in the U.S. and Alcatel Submarine Networks (ASN) in France.

These top three vendors together hold about 90% of the market for submarine cable construction. Each has a “territory” of its own: the U.S. for SubCom, Europe for ASN, and Japan for NEC. Each company has local advantages, such as techniques for obtaining licenses and approval from the government, knowledge about the coastal topography, and connections with fishery operators. This helps them to win contracts.

Until its bitter experience with the Jupiter cable six years ago, NEC was involved in almost every major undersea cable project that landed in Japan. However, the Jupiter contract, awarded in bidding in the autumn of 2016, went solely to SubCom.

NEC executives at the time said that the company had lost on price, lamenting it as “NEC’s only defeat.” But some in the industry had a different view.

The consortium that ordered the construction of Jupiter was composed of six companies, including Meta (Facebook), Amazon.com, Nippon Telegraph and Telephone Corporation (NTT), and SoftBank. SubCom won a separate cable project funded by Meta around the same time, and there were rumors that Meta backed SubCom, its favored vendor, in the bidding for Jupiter.

In October 2021, however, NEC won a contract from Meta for a trans-Atlantic cable, and construction began. It was the first time for NEC to provide a trans-North Atlantic cable. How was NEC able to rebound after its 2016 rout, win over its rival’s former benefactor and break into the previously untouched territory?

Competing on capacity

The new trans-Atlantic cable will connect the U.S. and Europe and is set to be completed between 2023 and 2024. Its name, total length, and landing locations have not been disclosed, but it is expected to be able to transmit 500 trillion bits per second. This exceeds the capacity of the Juno cable (350 trillion bits per second) that was announced in July 2022 by NTT and Mitsui. That cable — another project that NEC won — currently has the largest capacity among trans-Pacific cables.

500 trillion bits per second would enable the transmission of 13,300 Digital Versatile Disc worth of data every second, meaning about 25 million people could simultaneously watch YouTube 4K videos. This ultra-high capacity was the decisive factor in winning over Meta.

“There were various factors that let NEC win the contract with Meta, but I think the very high capacity played an important part,” said Takahiro Kashima, manager of the submarine network division at NEC. “Other companies are also starting to introduce this a year after us, so I think NEC’s proposal was a good one.”

Once placed at the bottom of the ocean, there are no occasions to improve or upgrade submarine cables. From the late 2000s through the 2010s, a period known as the “winter” of undersea cables, transmission capacity grew 20-fold, but only through improvements to onshore facilities.

Those upgrades to land-based facilities had “almost reached their limit” around 2018, said Kashima. Around that time, a cable-building boom, spurred by U.S. IT giants like Google and Meta, took off.

Google and Meta are also investing in higher-capacity cables. “The demand is stronger for holding down the cost of transmission capacity per bit rather than the total investment amount for the undersea cable,” said Kashima.

So even if the price of a cable increases by 10%, the IT giants will choose a project if the transmission capacity rises by a greater amount and the cable become more efficient. This is also thought to be driving the cable vendors to develop new technology.

However, business with IT companies is not easy.

Previously it was taken for granted that a project was contracted as a whole, including the cable itself, the land facilities, and the work of laying the cable. But the IT companies segment large projects into several parts, ordering cables and onshore facilities from different companies while securing their own cable-laying vessels. This creates competition within each bid, and vendors find it difficult to profit unless they can raise prices through technological innovation.

Technological first

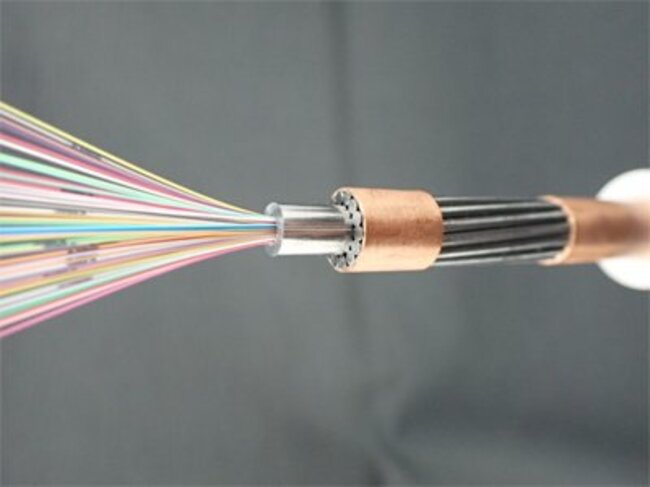

NEC was able to achieve 500 trillion bits per second thanks to its ability to place 24 sets (48 fibers) of optical fibers in a single undersea cable. A cable could hold only four sets in 2010 and 12 sets in 2020.

An optical fiber is about as thick as a human hair, but there is a different limiting factor: the repeater, which amplifies the signal that is reflected along the fiber.

Data signals gradually weaken as they travel along thousands of kilometers of cable, so repeaters need to be installed at intervals of less than 100 kilometers. The repeaters also help to determine the location of trouble or damage in the cable by showing how far a signal had traveled before it was lost.

Only repeaters of limited size can be loaded onto cable-laying vessels. The number of optical fibers that can be amplified by these repeaters is the most that can be included in a single cable.

In 2021, NEC became the first to commercialize a cable with 48 optical fibers because it was able to further miniaturize its repeaters. Having overtaken its rivals in this technology, it was able to win the contract with Meta.

NEC became the first to commercialize an undersea cable system that holds 24 sets, or 48 optical fibers, in 2021. Photo provided by NEC

NEC became the first to commercialize an undersea cable system that holds 24 sets, or 48 optical fibers, in 2021. Photo provided by NEC

The top three submarine cable vendors can all manufacture submarine cables and repeaters on their own.

There used to be more players in the undersea cable industry, including Japan’s Fujitsu, but many were reorganized or left the sector during the “winter” of submarine cables.

In 2008, NEC acquired OCC, a manufacturer of undersea cables and repeaters, together with Sumitomo Electric Industries. At the time, the deal was seen as a rescue package by the Sumitomo Group because OCC had received support from the Industrial Revitalization Corporation of Japan in 2004. Ultimately, however, the decision enabled NEC to remain in the industry and be placed among the world’s top three players.

“Having OCC within the group means a lot to NEC,” said Takahisa Ota, senior director of the submarine network division at NEC. “Both repeaters and submarine cables can be manufactured within the group, and development to increase their capacity and quality can quickly move ahead.”

Competitors catching up

However, the top three are facing a new challenger: HMN, a company originally created as the undersea cable sector of China’s Huawei Technologies in 2008.

Huawei sold HMN — then called Huawei Marine — to Hengtong Group, the leading telecommunications company in China, in June 2019 due in part to pressure from the U.S. The company was renamed HMN Technologies, but it continues to use devices manufactured by Huawei.

HMN is winning an increasing number of contracts, mainly in Africa, and in 2021 it made a bid for the World Bank-led East Micronesia Cable in the Atlantic Ocean by offering the lowest price. Because the cable was planned to reach Guam, the U.S. voiced security concerns, and the bid was nixed.

HMN’s cables are relatively short, and they are usually laid in shallow waters. The company also has yet to prove it can lay a durable cable with a lifespan of 25 years. As a result, many in the industry still feel they cannot entrust large projects like trans-Pacific or trans-Atlantic cables to HMN.

Ota, however, is paying attention. “HMN is quickly catching up in terms of price competitiveness and technology. It also has abundant resources, and you can never underestimate its strength,” he said. “Although it’ll likely be difficult to win contracts for cables connected to the U.S., competition will increase in neutral countries [in the confrontation between the U.S. and China]. The company will become stronger by accumulating experience in winning contracts.”

NEC completed SACS, a submarine cable project crossing the southern Atlantic, in 2018 and CANI, a project in the Indian Ocean, in 2020. The company is advancing into markets beyond Japan, its home turf, and is aiming to become the top of the field. It is muscling into the huge market of the Atlantic, where SubCom and ASN engage in fierce competition, starting a full-blown battle among the top three in the undersea cable industry.

(Originally written in Japanese by Hiroyuki Oya, translated into English by Erklaren Inc., and edited by Connor Cislo)